WA and Public History

History plays a rich role beyond academia in Western Australia. Diverse audiences concerned with history are served by a range of organisations, including the Royal Western Australian Historical Society, the National Trust of Australia (WA), Family History WA, the WA History Council, the Oral History Association (WA), Heritage Council WA and many local entities, from the University of Western Australia’s Centre for WA History to suburban and regional historical societies and small museums around the State.

There is an active branch of the Professional Historians’ Association (PHAWA) whose members undertake commissioned histories for a range of clients, including State and local government agencies, not-for-profit organisations, community history societies, the National Trust WA, private businesses, churches, museums and various heritage property owners. Historians frequently work within multidisciplinary teams alongside specialists such as curators, graphic designers, media officers, architects, town planners and archaeologists. Many current PHAWA members work within the heritage industry, often sub-contracting to architects, with the actual clients generally being property owners. Heritage work ranges from brief historical sketches supporting planning application to comprehensive thematic studies of whole areas of WA history, but is fundamentally place-based. Members of PHAWA include historians who work in salaried positions rather than on commission, primarily in government, at State or local level, and often linked to heritage, museums or libraries. Notably, Dôme cafés and coffee has an historian on staff as part of their program of adapting heritage buildings for coffee shops and boutique hotels.

In 2020 the Western Australian Museum Perth site re-opened after a major redevelopment, and was re-named WA Museum Boola Bardip, meaning ‘many stories’ in Noongar language – acknowledging the First Peoples and aiming to represent the shared history of all Western Australians. The State Library of Western Australia and the State Records Office of Western Australia, which share a single building, play an important role in fostering historical consciousness and research across the state, including through its staff. Innovative programs aiming to return collections to Aboriginal communities are breathing new life into collections and into public history in this State. The State Library’s Storylines program provides a digital access and engagement platform, returning digitised collections to Aboriginal families and communities and re-describing collections from the perspective of Aboriginal people. New collections have come to light through this form of public history work, such as the highly significant Mavis Phillips (nee Walley) Collection, as well as new understanding of known collections. The Heritage Council of WA, supported by the Heritage Services branch of the Department of Planning Lands & Heritage, administers the State Register of Heritage Places, including management of world heritage listed Fremantle Prison, and contributes to protecting and promoting history and heritage across the State.

The National Trust of Western Australia (established in 1960), works to raise understanding of the state’s past through the conservation and interpretation of the heritage places it manages, through education and learning programs, and through community consultation and engagement. For example, the Trust also manages the Golden Pipeline Heritage Trail which runs from Mundaring Weir east of Perth inland to Kalgoorlie-Boulder, commemorating the great Goldfields Water Supply Scheme: in 1896, following the struggle for water in Coolgardie and the Kalgoorlie-Boulder region, Premier Forrest introduced a scheme to build a 500km pipeline from a dam on the Helena River near Mundaring. During the 1950s a significant collaboration between UWA historians and the state government established that C.Y. O’Connor initiated the project, and saw it to completion, and an annual named lecture in his honour continues to be hosted by the Trust (Witcomb & Gregory 2010).

Between 2003 and 2009, a team of nearly 600 contributors and expert readers, as well as an Editorial Advisory Board of twelve, an editorial staff of two, and a number of support staff, worked to produce the Historical Encyclopedia of Western Australia, a major work of historical reference. WA has a distinctive tradition of institutionally-commissioned histories, which complements the historiographical tendency to localise, through producing political, economic or settler histories reflecting larger ‘Australian’ themes, but focusing on WA (Maddern 2012. See also Bolton 1972: 3). In 2014, for example, the WA company Wesfarmers celebrated its centenary, including a major history of the company, The People’s Story 1914-2014 by Peter Thomson, a free concert in rural Northam by the West Australian Symphony Orchestra and the West Australian Opera, and a gala Annual General Meeting. UWA Press, Fremantle Press and Magabala Books all publish Western Australian histories, the latter focussed on Aboriginal history and culture.

Popular forms of history-making are represented on social media platforms such as the Facebook groups ‘Lost Perth’, ‘Lost Albany’ and ‘Lost Broome’, which share images and memories from recent decades, playing to a widespread nostalgic sensibility. Both the State Library and State Archives regularly post historical insights from their collections via Facebook. Many listen to both the ABC 720 Perth radio segment ‘History Repeated’ which features State Library and State Records Office historical collections and shares stories about WA history, as well as 6PR’s long-running and popular Sunday night ‘Remember When’ program.

The 1970s saw a tremendous upsurge in popular interest in local and regional history, fostered both by government and heritage bodies such as the National Trust. A unique project was mounted aiming to produce a Biographical Register of all Western Australians to 1914. The oral history program expanded at the Battye Library, capturing the voices of everyday people and providing a glimpse into the memories and folklore of Western Australians. The Oral History Association of WA formed in 1978, followed the following year by the WA Genealogical Society. The Western Australian Museum (WAM) began opening regional branches in 1968 at Kalgoorlie, and later also Albany, Geraldton and Fremantle. Through the 1970s WAM also ran a program to provide expert advice for the establishment of municipal museums, prompting the establishment of museums at York, Claremont, Cunderdin, Wongan Hills, Geraldton, Yalgoo, Armadale and Esperance. Social history gained momentum, and during the 1970s a new focus on Aboriginal history and relations with colonists emerged, including work by anthropologists and archaeologists based at WAM. The 1979 Sesquicentenary of colonisation stimulated an increased historical awareness, expressed through ‘pioneer’ family reunions, publication of local histories and a state-commissioned 14 volume series of thematic studies covering a wide range of topics. Hotham Valley Railway commenced as a tourist line in 1977, six years after the last commercial steam engine in WA was retired. Yarloop Railway Workshops closed in 1978 and were taken over by the community to be converted into a rail museum.

By the 1980s more controversial aspects of their history were making an impact on the public, as revisionist histories challenged the popular celebration of WA’s ‘pioneer’ origins (See Stannage 1979). The State’s troubled colonial past - as elsewhere across the continent - was characterised by violence between colonists and First Nations peoples, and remains contested. An intriguing response has been the phenomenon of ‘dialogical’ monuments, where memorials commemorating colonists’, Euro-centric perspectives have been supplemented and challenged by later additions: at Cossack, a former pearling centre in the north-western Pilbara region, a sign which celebrates the industry has been challenged by the addition of interpretation expressing the Indigenous perspective on this history of labour exploitation and discrimination (Gregory & Paterson 2015). Similarly, a 1913 public memorial in Fremantle, memorialising colonial explorers who died as part of Aboriginal resistance to colonisation, was supplemented in 1994 by a second plaque challenging the colonial perspective and acknowledging Aboriginal people killed in frontier wars (Pettitt’s Blog; ABC Article). Noongar people have strongly asserted the significance of frontier violence, such as the Pinjarra Massacre of 1834; likewise the Kukenarup massacre memorial near Ravensthorpe was established by the local historical society in 2015 after they were approached by Noongar descendants of the survivors. At Dimalurru/ Tunnel Creek in the Kimberley, interpretation of the history of resistance led by Jandamarra, known as the Bunuba wars, is now on display.

In 2016, Noongar traditional owners of the State’s South West agreed to the largest Indigenous Native Title land settlement in the nation, prompting extensive research into Indigenous history and culture. Important linguistic reclamation and revitalisation work has been undertaken, led by Noongar scholars such as Kim Scott and Clint Bracknell. However, during the ‘History Wars’ of the turn of the millennium, Indigenous and professional expressions of public history which assert Aboriginal experience continue to be opposed in less formal forums, including social media. For example, Rob Moran’s 1999 Massacre Myth alleged the 1926 Forrest River Massacre in the Kimberley never happened.

Before 1950

An interest in collecting ‘natural history’, motivated by intellectual curiosity as well as economic potential, was a feature of Europeans’ earliest encounters with Western Australia, producing collections now distributed across the globe. Navigator William Dampier, for example, was tasked by the British government to make the first plant collection in 1699, within the Enlightenment encounter with diverse world cultures and histories. Geological collecting was central to promoting the colony’s natural resources to the rest of the world through display at International and intercolonial exhibitions, beginning with the Great Exhibition in 1851 (Zylstra 2020). An interest in geology was further stimulated by significant gold discoveries between 1885-1893, and has continued to characterise popular histories.

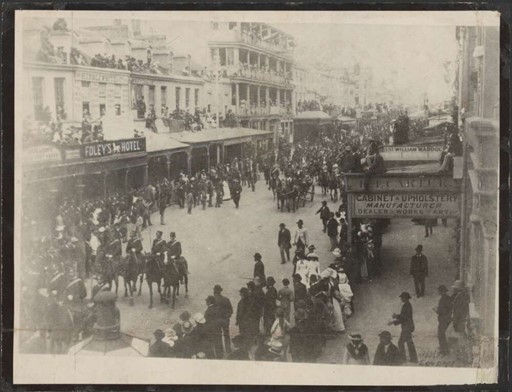

A popular historical consciousness was fostered by Western Australia’s colonial government from the mid-nineteenth century. When Perth’s Swan River Mechanics Institute was established in 1851, it shared the global movement’s goals to educate working-class men through library, lectures, and discussion – and in WA was seen as a counter to the convict presence (Stannage 1979: 137-138; Cook & Witcomb 2020). Coinciding with the achievement of responsible government in 1890, in 1891 the Geological Museum was established, to which Aboriginal and natural history exhibits were quickly added. As the 1890s gold boom increased population and diversity of cultural expression, and filled government coffers, the government supported establishment of cultural institutions. In 1897, the museum officially became the Western Australian Museum and Art Gallery, and in 1913 was also combined with the State Library. During 1959, the botanical collection was transferred to the new Western Australian Herbarium and the museum, state library and art gallery became separate institutions. The museum focussed its collecting and research interests in the areas of the natural sciences, anthropology, archaeology, and Western Australia’s history. During the 1960s and 1970s, it also began to work in the areas of historic shipwrecks and Aboriginal site management.

At the time of the colony’s fiftieth anniversary in 1879, Edmund Stirling, editor of the Inquirer and a senior colonist, called for ‘a narrative from authentic sources of our progress’ and glowing future prospects, perhaps seeking to promote immigration. Stirling published the first volume of his account, A Brief History of Western Australia, in 1894, covering the period 1827- 1842, and structured by themes of colonial toughness and resilience – and blame of outside governance for any problems (Gregory 2020: 1-18).

The many shipwrecks along WA’s coast dating from the seventeenth century have also been a popular subject for public memory, such as the horrifying story of the 1629 shipwreck of the Batavia off the coast of Western Australia, followed by mutiny and the massacre of many survivors. An illustrated book, or pamphlet, Ongeluckige voyagie, van’t schip Batavia (Unlucky voyage of the ship Batavia) was published in Amsterdam in 1647, catering to a large international audience and helping to shape a new genre of shipwreck narrative (Lyndon 2018: 351-374). In 1897, a time of nationalist debate leading up to Federation in 1901, its first English translator Willem Siebenhaar suggested that this “earliest of Australian books” told the story of “the first settlers — involuntary, it is true — in Australian territory” (Siebenhaar 1897: 5-7). As an alternative national foundation myth, the Batavia narrative reveals the cosmopolitan networks characterizing this region from the sixteenth century, and undermines the narrative of fatal British impact in the east.

During the 1890s as the colony asserted its new place within the nation and the empire, major histories were sponsored by the government. American Warren Bert Kimberly produced a ‘commemorative history’, including a series of biographical sketches of leading citizens. Premier Sir John Forrest sponsored the project, and Kimberly adopted a consensual interpretation that played down social conflict and emphasised the colony’s material progress, especially the galvanising effect of gold discovery (Bolton 1981: 677-680). Following closely in Kimberly’s footsteps, state librarian J.S. Battye produced both a 1913 history, the Cyclopaedia of Western Australia, and a 1924 History of Western Australia, also officially sponsored. These commissioned works conformed to myths of progress and a pioneering gentry class, omitting the convict period and conflict with Aboriginal people.

In 1923 Battye chaired a public records committee, which supervised the transfer of archives into a central repository. The 1929 centenary celebrations also emphasised progress, the State Archives Board was created, and for the first time WA was depicted as a significant contributor to the British empire. In 1926 a group formed what is now the Royal Historical Society of Western Australia – launching a journal, Early Days.

In 1945 custody of the state’s archives was vested in the Public Library under the management of Mollie Lukis, and many public and private archives were lodged with what became the Battye Library in 1956. Following her Carnegie Fellowship in America, Lukis also established the oral history program in 1961 at the Battye Library - thought to be the earliest oral history program established in an Australian collecting institution. Paul Hasluck also conducted oral histories with elderly colonists, nearly 50 years before the invention of the tape recorder. Remembered as a statesman and Australia’s 17th Governor-General, Hasluck trained and worked as a journalist and historian before entering politics, and in retirement was a prolific author, publishing an autobiography, several volumes of poetry, and multiple works on Australian history. Writers and historians such as Alexandra Hasluck and Mary Durack produced vivid popular accounts of the colonial period and settler biographies (Bolton 1981: 687). During the 1950s a series of studies of local industries were produced, especially agriculture, marking the start of this distinctive WA tradition.

Bibliography

Books, Chapters and Articles

Geoffrey Bolton, A Fine Country to Starve in, Perth: University of Western Australia Press in association with Edith Cowan University, (1972).

Geoffrey Bolton, ‘Western Australia Reflects on its Past’, in C.T. Stannage (ed), A New History of Western Australia, Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press, (1981): 677-680.

Denise Cook and Andrea Witcomb, ‘The Natural History Collections of the at the Swan River Mechanics’ Institute: Origins,Role and Legacies’, Studies in Western Australian History 35 (2020): 89-109.

Jenny Gregory, ‘Commemorating Milestones in Western Australian History’, Early Days: Journal of the Royal Western Australian Historical Society 104, (2020): 1-18.

Kate Gregory and Alistair Paterson, ‘Commemorating the colonial Pilbara: beyond memorials into difficult history’, National Identities, Routledge, (2015).

Jane Lydon, ‘Visions of Disaster in the Unlucky Voyage of the Ship Batavia, 1647’, Itinerario 42(3), (2018): 351–374.

Willem Siebenhaar, ‘The Abrolhos Tragedy’, Western Mail (Christmas Number), (24 December 1897): 5-7.

Tom Stannage, The People of Perth: A Social History of Western Australia’s Capital City, Perth: Perth City Council, (1979).

Andrea Witcomb and Kate Gregory, From the Barracks to the Burrup: the National Trust in Western Australia, Sydney: University of New South Wales, (2010).

Baige Zylstra, ‘“Those riches of which we are so proud”: Western Australian geological collecting for international and intercolonial exhibitions 1850-1890’, Studies in Western Australian History 35 (2020): 59-74.

Lectures

Philippa Maddern, ‘“The Past Is Not What It Used to Be”: The Future of Western Australian History’, History Council of Western Australia Annual Lecture (2012).

All content on the blog is distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).