Overview

The island state of Tasmania has a complicated relationship between culture, conservation and development. Van Diemen’s Land, the first European settlement on the island, was established as a penal colony, and with that came an international reputation of low class, illiteracy and criminality. Even in the twenty-first century, nearly half the population remains functionally illiterate (lacking the reading, writing and mathematical skills required for everyday tasks). Despite – or perhaps in spite of – this there has been a long history of public cultural institutions in Tasmania.

Every year, barring the Covid-19 restrictions, Tasmania welcomes tourists from around Australia and the world. In the 2018-19 season, 1.4 million guests visited the state, with another 130,000 arriving on cruise ships. 357,411 people visited the Port Arthur Historic Site on the Tasman Peninsula. Thousands of guests visited other sites under the Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority (PAHSMA) – the Cascades Female Factory, Ross Female Factory or Saltwater River Coal Mines – to see the places their convict ancestors were imprisoned, while others went straight to the archives to research. With Tasmania’s long convict history, extensive records, and massive digitisation projects, family history research is an expanding tourism market. PAHSMA employs and engages professional historians at all stages of developing their site interpretations, from the initial research through to the final exhibitions.

Public history in Tasmania focuses primarily on the European histories of the island, largely by habit. There is, however, a growing effort to tell authentic Indigenous histories; the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery has redeveloped their permanent Tasmanian Aboriginal exhibition, ningina tunapri, and opened another (also permanent), ‘Our land: parrawa parrawa! Go away!’, that tells the story of the European invasion through Aboriginal eyes. In the north-west, a palawa-run business tells its guests that ‘the palawa people did not document their history or keep it in museums – this landscape is their museum’ as it invites them on a three-night walk through the landscape of larapuna / Bay of Fires and wukalina / Mount William. While the price tag on this experience means it is beyond the access of most of ‘the public’, it is part of an expanding network of Tasmanian Aboriginal storytellers using their voices to share palawa histories.

In 2021, the winter festival Dark Mofo cancelled a particular work that would use Indigenous blood as a medium for art after its announcement caused mass public outrage (see the news article here). This suggests that there is a growing reluctance among Tasmanian and national consumers of culture to engage with art that misappropriates or misrepresents First Nations histories.

Museums

Visitors to the colony in the early days expressed dismay at what they perceived to be a widespread lack of opportunity for cultural betterment. That was not for a want of awareness or effort – free settlers brought with them aspirations of belonging to an educated population. In 1827, Australia’s first mechanics’ institute was opened in Hobart Town, with others following around the island throughout the rest of the century. Intended to provide opportunities for education for working class men, they tended to exclude this audience and instead attracted middle class men and women. In 1843, the Royal Society started to consolidate the scientific and cultural artefacts held by mechanics institutes and private collectors. These collections formed the core of the early Tasmanian Museum, which became the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in 1889 with the construction of a wing for art. In the 1850s, this institution started to open longer hours and in 1855 attracted ‘upwards of 1000 visitors’ during the year (Bryden 1966).

On 15 February 2021, the Royal Society of Tasmania and the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery issued a joint apology to the Tasmanian Aboriginal people for the theft and desecration of cultural and ancestral remains that had been conducted by them and in their names throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Koolhof 2021; Torossi 2021).

Today, the largest history museums in Tasmania are the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) and the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (QVMag), with combined visitor numbers exceeding 500,000 in 2018-19. The Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) includes some historical exhibits, but is not focussed on exploring historical themes or stories. Smaller museums and heritage centres can be found in every town, celebrating the local area or specific themes. The National Trust is active in Tasmania, although they only advertise eight properties in the state, so their reach is somewhat limited. TMAG manages two house museums in Hobart, Narryna and Markree, and local councils manage other sites, such as the former defensive batteries along the Derwent which have been turned into parks. Many of these houses and sites are popular as venues for exhibitions and art installations, or private functions. Most, including the parks, display at least some basic information about the history of the site, although this author doubts many read the signboards.

Volunteering

As with all GLAM institutions, heritage in Tasmania is reliant on volunteer hours to keep buildings open and operating, to develop exhibitions, and to manage the administration or collection duties that continue unseen. One example of the public history volunteers is the family history helper in Libraries Tasmania. These individuals can be booked for a session to help researchers start or continue their search for their family history. The assistance they and the regular staff offer to visitors is in high demand.

There is an interest in both presenting history to the public, and providing opportunities for individuals to engage behind the scenes and develop their curating skills. As one example, the Collection of Medical Artefacts in Hobart engages humanities students from the University of Tasmania as volunteers to catalogue and digitise their objects. The University also offers industry partnership scholarships for honours students, with some available projects connected to heritage and history organisations. In 2021, students are working with the Tasmanian Archives and with local museums through Heritage Tasmania.

Organisations

The Professional Historians of Australia has a small presence in Tasmania, within the combined branch of Victoria and Tasmania. There are ten registered professional members in the state, but the organisation collaborates with the wider professional historical community by hosting monthly public history talks at the Allport Museum in Hobart.

Tasmania has several large historical societies, along with numerous local heritage and family history groups. The Tasmanian Historical Research Association (THRA) was formed in 1951, replacing several other societies. THRA continues today and is based primarily in Hobart. It holds monthly public talks that are well-attended (and further enjoyed in recorded form online) and regular excursions to sites of historic interest. The Launceston Historical Society was established in 1988, and continues to perform the same role in the north of the state.

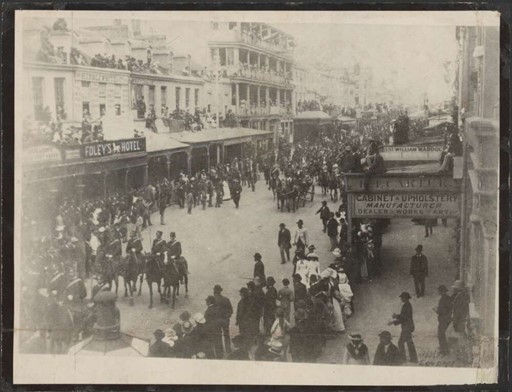

For several reasons, including the state’s convict heritage and its demographic, many Tasmanians have an interest in researching their family history. This is one of the main forms of history practised by the public, and its traces can be found everywhere. From the family history libraries and society branches scattered across the island, to the shelves of self-published biographies in the independent bookshops, the interest is high. Until the mid-twentieth century, having a convict in the family tree was considered somewhat shameful. Today, however, it is a point of pride and it is not unusual to see people peering intently at the names on memorials, such as the Convict Brick Trail running through Campbell Town in the Tasmanian Midlands (see image above). Many visit hoping to find the name of their ancestors listed.

References

- W Bryden, ‘Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery: Historical Note’, Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 100 (1966): 23.

- Mary Koolhof, ‘Apology by the Royal Society of Tasmania to the Aboriginal People of Tasmania’ (Hobart, Australia, 15 February 2021), https://rst.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/RST-2021-Apology-to-Tasmanian-Aboriginal-People-for-the-web.pdf

- Brett Torossi, ‘Apology to Tasmanian Aboriginal People’ (Hobart, Australia, Department of State Growth, 15 February 2021), https://www.tmag.tas.gov.au/about_us/apology_to_tasmanian_aboriginal_people.

All content on the blog is distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).