Sydney’s Nineteenth Century Gymnasium Network

Part 2

Now that we understand how the gymnasium functioned, let’s have a look at how recreation, health and entertainment were reflected in these gymnasiums…

This is Part 2 of a series (Part 1)

Miss Foster’s Ladies Gymnasium

Miss Foster’s Ladies’ Gymnasium once stood directly opposite Hyde Park at 177a Liverpool Street, next to the Unitarian Church. What remains is an office complex consisting of a medical centre, café and law firm; it appears that the original building was refurbished in 1920 (City of Sydney 1920).

From the little information available about Miss Mary Foster, we know that she was the former principal of The Melbourne Ladies’ Gymnasium in Flinders Street, overseen by Miss Elphinstone Dick. She was a gymnastic instructor at the Wesleyan Ladies College, Burwood and Modera High School (Sands Postal Directory 1887).

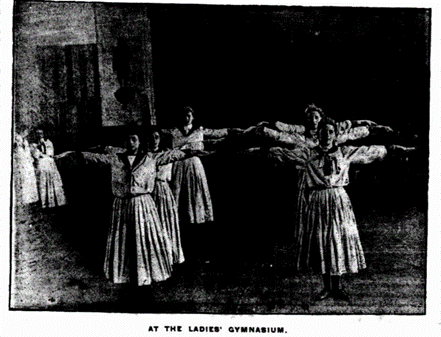

A notable event for Mary Foster was the visit of Lady Carrington – wife of N.S.W. governor Sir Charles Carrington– in 1888 to the gymnasium, where forty pupils performed a demonstration of physical activities involving dumbbells, Indian clubs and marching (The Daily Telegraph 1888, Illustrated Sydney News 1889). Following this visit, local newspapers began writing articles about the gymnasium. The article mentioned at the beginning of this blog post focused on connecting the girls to Spartans, explaining the new muscle therapy, the ‘Ling Cure Movement’, and how the girl’s flannel gym costumes revealed both ankles and stockings! (Illustrated Sydney News 1889). Might I just add that this is the first time – as a student of nineteenth-century European history – that I have come across an actual example of the Victorian ankle ‘taboo’ in my research.

Miss Foster went on to supervise the construction of a new gymnasium at the Wesleyan Ladies College in 1891 and continued operating the gymnasium until early 1892 when the business suddenly transfers to Miss Elphinstone Dick (The Daily Telegraph 1891, The Sydney Morning Herald 1892). It is at least a decade until Miss Foster is mentioned again, this time as a physical trainer at the Lotaville School at Randwick, and then in 1905, Miss Foster established the Swedish and Medical Gymnastics located in a Hyde Park church hall (The Daily Telegraph 1902, The Daily Telegraph 1905).

Beneath the mythology and unrealistic ideals surrounding women’s fitness, Mary Foster continued to emphasise the therapeutic benefits that the gymnasium provided to women and girls. Mary continued to open new gymnasiums in New South Wales, and knowing of her connections with instructors in Victoria, the Sydney community was part of a broader early gymnasium network. Let’s go and see what was happening at the gymnasium next door…

Cansdell’s Sydney Gymnasium

175 Liverpool Street, Hyde Park, neighbouring the Ladies Gymnasium, was the site of one of many venues where fighter and gym instructor Professor Harry M. Cansdell hosted wrestling competitions in the late nineteenth century. Located in the basement of the Unitarian Church, the Sydney Gymnasium was managed by Harry Cansdell, in partnership with Professor G.H. D’Harcourt who appeared to have owned the business during the late 1870s (The Sydney Morning Herald 1882).

The gymnasium offered a vast array of physical activities and competitions involving fencing, Indian Clubs, and weightlifting; where parents and friends of Cansdell’s pupils could spectate (The Sydney Morning Herald 1882, Australian Town and Country Journal 1883). There appears to be one occasion at the Sydney Gymnasium where a social event attracted at least four hundred spectators, and included even more activities such as rope climbing, trapeze, rings and tug of war: meeting frequent applause from crowds (The Daily Telegraph 1884).

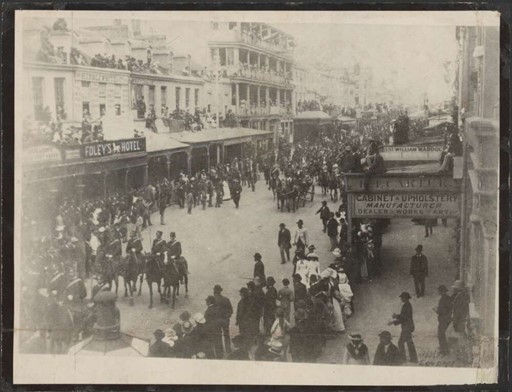

The site was vacated in 1885 in favour of a new gymnasium at the White Horse Hotel at 430 George Street, managed by retired champion Laurence ‘Larry’ Foley; it is said that the venue had a seating capacity of sixteen hundred (Evening News 1885). Cansdell became an instructor at Foley’s Sydney Gymnasium, and it was not long until he was in the ring against American wrestler ‘M’Caffrey’. Cansdell used a ‘Nelson lock’ -where the opponent lies on his stomach and is flipped onto his back – followed by a ‘French hug’ hold from M’Caffrey; Cansdell prevailed after thirty minutes (Globe 1886).

Throughout the 1890s Cansdell would manage his own gymnasium on Liverpool Street, Foley’s Sydney Gymnasium, and instruct at multiple venues, including the Sydney Amateur Gymnasium on York Street and the Y.M.C.A. Gymnasium on Pitt Street (The Daily Telegraph 1887, The Australian Star 1888, T_he Sydney Morning Herald_ 1889, Referee 1892). After the closing of the Sydney Amateur Gymnasium, Harry lobbied for successive governments to introduce gymnastics in public schools and offered his guidance to coordinate the programs. It’s unclear if the government considered Harry’s concept seriously, or whether he was unlucky to find a responsive interest or perhaps the concept was dismissed (Referee 1912).

While I can’t confirm if his lobbying eventually had an impact on future government initiatives on physical education in schools, Harry should be recognised for his efforts.

Let’s head now towards the Queen Victoria Building and have a look at what is left of the Sydney Amateur Gymnasium…

Belisario’s Sydney Amateur Gymnasium

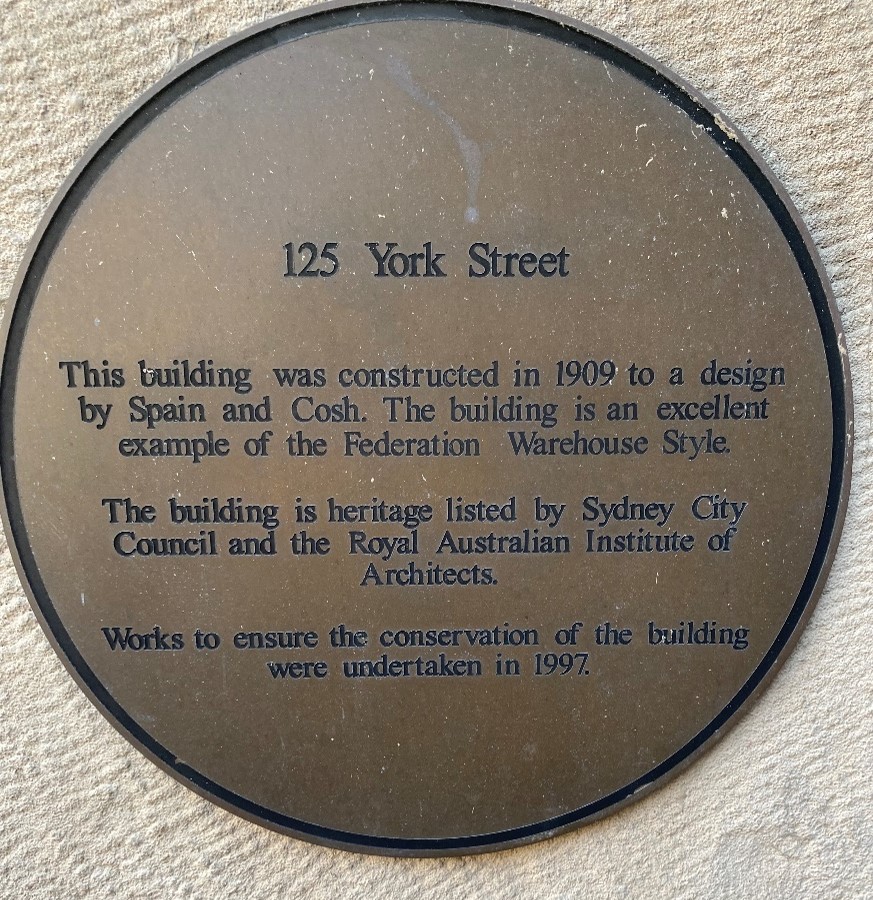

The Sydney Amateur Gymnasium was located at 125 York Street, opposite the Queen Victoria Building. You would think that being so close to the Q.V.B., the building would be preserved, and that is partially correct. What stands today is a building occupied by offices and restaurants. Designed in the ‘federation warehouse style’ and constructed in 1909 as mentioned on this plaque:

Just after thirteen months in business, the police intervened during The Sydney Amateur Gymnasium’s first unofficial prize fights. The fighters, George Dawson and James Burge were held on remand at Central Police Court for fighting each other until exhaustion which was unlawful (Evening News, 1890). Referee Sydney Bloomfield gave a statement defending the young gymnasium. Bloomfield argued that the club fostered athletics and promoted displays amongst members and professionals for trophies; the contests were open for all friends and members (Evening News, The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 1890).

E.H. ‘Ted’ Belisario was described as possessing a strong personality, as president of the club and referee on occasion for several matches with the Attorney-General of New South Wales Jack Want in attendance (The Sun 1915). Competitions held at The Sydney Amateur Gymnasium gained international interest from North America and England for their first-class fights with stars such as Billy Murphy, Jim Burge, Mick Dooley, Joe Choynsnki, James ‘Jem’ Mace, Robert ‘Bob’ Fitzsimmons and Albert ‘Griffo’ Griffiths, entering the boxing ring for spectators to see for a couple of shillings to a pound (Referee 1891, The Australian Star 1891).

The death of boxer Ike Stewart in 1914 spurred government action to suppress professional boxing, because while the sport had its fans, there was opposition from lobby groups, calling boxing ‘brutal and degrading’ (Truth 1940). Returning to Australia after a decade in America, former heavyweight champion of Australia, Peter Jackson reminisced about the Sydney Amateur Gymnasium, and how he barely recognised anyone from those early days as he stood on the corners of Market and George streets (The Sun 1915). For Ted Belisario, his prominence faded towards the early twentieth century, passing away in 1915, and the management of the Sydney Amateur Gymnasium passed to George Seale (The Sun 1915). Management changed frequently, and the site was made vacant in 1940 and became a ‘two-up school’ like other deserted gymnasiums in the area (Truth 1940).

The entertainment factor that the gymnasium provided not only fostered competitive athletes locally and internationally, but communities were being made within these spaces where anyone could participate, as either an athlete or spectator. On occasion, activities at these venues attracted the attention of police and anti-boxing lobbyists, a reminder that the gymnasium was unfortunately where unlawful activities and violence did appear (Waterhouse 2009, 104).

Foley’s White House Hotel and Gymnasium

Fighter, promoter and hotel manager, Lawrence “Larry” Foley, owned the White Horse Hotel and Gymnasium at 430 George Street from 1885 - 1898. Today the Dymocks building stands where the White Horse Hotel stood, however, newspaper articles from the early to mid-twentieth century claim that the gymnasium was where the Strand Arcade is currently. Both these buildings were operating simultaneously, so what’s with the confusion? I was able to find an article where this confusion was generated, and I am confident that the address mentioned above is where The White Horse was actually located (Sydney Sportsman 1907). Like Belisario’s Sydney Amateur Gymnasium on York Street, nothing remains of Foley’s Gymnasium.

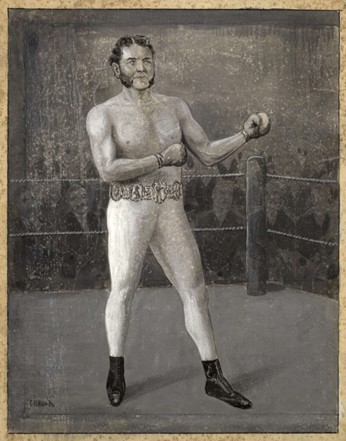

By the age of 19 Larry was said to be good enough to challenge, and win, against fighter Sandy Ross in a bare-knuckle fight at Port Hacking in 1871 (The Daily Telegraph 1917). Foley’s success continued into the 1870s, against competitors including Stonewall Jackson, Charley Kelly, Huges, Hogan, Johnson, Dick Brierley, Ben Wood, Corbitt, and Fagan; eventually, these victories earned Foley the title ‘Champion of Australia’ by 1880 (Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate 1880, Evening News 1880, The Daily Telegraph 1917). The United Service Hotel on Willam Street became Foley’s first gymnasium, and upon pledging to his spouse that he would never fight again, he continued issuing challenges to any middle or heavyweight fighter in Sydney (The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express 1879).

The first challenger, Abe Hicken, was defeated after a one-hour boxing match with Foley at the Watt-street Theatre, Newcastle in 1880; the bout reaffirmed Foley as a ‘good boxer’ before confronting the second challenger, Professor William Miller (Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate 1880, Evening News 1880, The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express 1883). The ‘Australian Hercules’ and ‘Champion Wrestler of the World’, Professor William Miller, accepted Foley’s challenge in 1883 and the two fought for forty rounds, the match lasting for three hours, and became most memorable not only for its duration length but also, the resilience and determination of both champion fighters to entertain the crowd with their physical prowess (The Sydney Daily Telegraph 1880, Newcastle Morning Herald and Miner’s Advocate 1883, The Daily Telegraph 1917).

Foley went on to own the White Horse Hotel in 1885, where the venue bouts and trained Sydney’s boxing celebrities including Peter Jackson, Bob Fitzsimmons, Jem Mace and Griffo (The Daily Telegraph 1917). The venue was demolished in 1899, but by that time Foley continued to instruct, manage and on occasion fight, notably against the first African American world heavyweight champion Jack Johnson in three exhibition matches at Queen’s Hall, and a charity match at Manly Skating Rink between 1907 – 1908 (The Arrow 1907, Sunday Times 1908). Foley entered the political sphere through his work as a contractor, working closely with the Minister of Public Works to demolish buildings in Sydney’s CBD, such as the ruins of Her Majesty’s Theatre on the corner of Pitt and Market Street, and he ran for state parliament as the member for Yass in 1904 unsuccessfully (The Daily Telegraph 1902, The Hillston Spectator and Lachlan River Advertiser 1903).

Larry Foley’s career revealed to me just how vital networking was between the White Horse Hotel and the Sydney gymnasiums as the centre of athletic talent. The list of famous Sydney wrestlers and boxers training at the gymnasium appears endless, with an owner who engaged with the public area his entire life through many forms, as an athlete, manager, and political figure.

It felt weird standing opposite the Dymocks building trying to imagine the White Horse Hotel. I couldn’t seem to grasp my bearings, imagining all the things that happened here. There simply wasn’t a way to clearly recognise a landmark or a plaque that at least recognised that this site was once the centre of Sydney’s early gymnasium community and athletic network.

What these gymnasiums shared was establishing a democratic space to foster community engagement with athleticism, accessible to both athletes and spectators, for health, recreation, and entertainment (Carden-Coyne 1999, 138). These communities allowed for the improvement of the venues, the quality of athletes and thereby expanding the gymnasium networks across the Sydney CBD. Where do we go from here?

At every turn throughout my research, there were always links connecting one gymnasium to another. This demonstrates the strength of the network of athletes and owners within the Sydney CBD at the time. As the century turned, this community was gradually overtaken by Sydney’s redevelopment. There were many other owners of this nineteenth-century community that I’d like to include, together with the athletes involved. I’ve just focussed on these four owners and their gymnasiums; and the spaces they shared of health, recreation, and entertainment typical of a nineteenth-century gymnasium in Sydney.

The owners, athletes and the places that were all once part of this active gymnasium community in Sydney’s CBD still have stories to be shared and need to be memorialised. I hope that my research internship, the database, and my findings will influence researchers to begin rediscovering the many owners, athletes and gymnasiums and Sydney’s broader history.

Bibliography

- Journal Articles

- Alexandra Carden‐Coyne, Anna. 1999. “Classical heroism and modern life: Bodybuilding and masculinity in the early twentieth century.” : Journal of Australian Studies, 23:63, 145-146.

- Waterhouse, Richard. 2002. “Bare‐Knuckle prize fighting, masculinity and nineteenth century Australian culture.” Journal of Australian

- Studies, 26:73, 101-110.

- Westberg, Johannes. 2018. “Adjusting Swedish Gymnastics to the Female Nature: Discrepancies in the Gendering of Girls’ Physical

- Education in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Espacio, tiempo y educación 5, no. 1 261–279.

- Images

- (1870) Hyde Park looking toward Liverpool St., 1870. SPF/892. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

- (1885) Larry Foley’s White Horse Hotel in George Street, Sydney, with the Sudan regiment passing by 1885. National Library of Australia.

- (1889) At the Ladies’ Gymnasium. The Illustrated Sydney News. Trove.

- (1920) Print - Commercial building in Liverpool Street Sydney. City of Sydney.

- Charles Henry Hunt (1875). Larry Foley. National Library of Australia.

- Robert Buttiglieri (2023). Photograph - 125 York Street. City of Sydney Council and the Royal Australian Institute of Architects.

- Newspaper Articles

- Australian Town and Country Journal “Ladies’ Pages.” December 1, 1888: 21.

- Australian Town and Country Journal “Notes by Nimrod” September 1, 1883: 36.

- Evening News “The Burge-Dawson Fight.” December 6, 1890: 5.

- Evening News “A New Gymnasium.” December 15, 1885: 3

- Globe “Cansdell v M’Caffrey.” January 2, 1886: 4.

- Illustrated Sydney News “The Ladies’ Gymnasium.” October 31, 1889: 28.

- Referee “Among the Boxers.” March 9, 1892: 6.

- Referee “Murphy v. Burge” November 25, 1891: 6.

- Referee “Harry Cansdell Dead” November 13, 1912: 7.

- The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express “Victorian Mems.” April 26, 1879: 17.

- The Australian Star “Dawson V. Mace” April 28, 1891: 6.

- The Daily Telegraph “Advertising” April 1, 1905: 13.

- The Daily Telegraph “Advertising” March 8, 1902: 2.

- The Daily Telegraph “The Sydney Gymnasium.” September 22, 1884: 8.

- The Daily Telegraph “Wesleyan Ladies’ College” January 9, 1891: 3.

- The Hillston Spectator and Lachlan River Advertiser. 1903. “Odds and Ends” October 16, 1903: 3.

- The Sun “Gossip of the Ring” June 13, 1915: 14.

- The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser “Glove Contests” December 13, 1890: 1332.

- The Sydney Morning Herald “Advertising” March 23, 1892: 2.

- The Sydney Morning Herald “Advertising” November 23, 1882: 2.

- Truth “The Life Story of Joe Wallis No 2” December 29, 1940: 19.