PCYC and Memory

In 2022, I completed my Masters of Research which focused on the appointment of women police in NSW. After a long year of delving into the history of policing in Australia a friend approached me asking what I knew about the Police Citizen’s Youth Club (PCYC). At the time, my only exposure to the club was my Tuesday night social netball team, but as someone who is interested in the historical dimension of policing, the history of PCYC certainly captured my attention. I was initially drawn to this project when thinking about the role of police in community led sports and what this meant for youth justice both in a historical context but also a contemporary one. However, once I began my research I became increasingly interested in the clubs and their relationships to their local communities. In particular, I was fascinated by how previous members of PCYC construct and mobilise a sense of a shared past.

History of PCYC

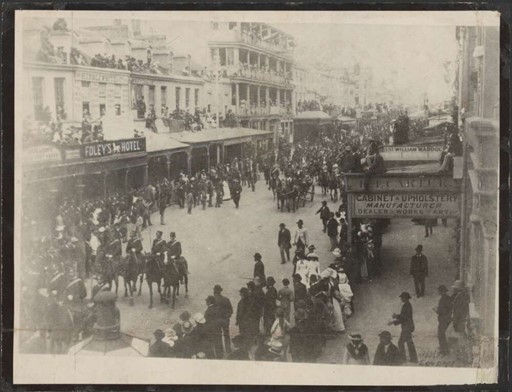

PCYC was first established as the Police Citizens Boys Club in 1937 in the Sydney suburb of Woolloomooloo. After observing successful boys clubs in his trip to Europe, NSW Police Commissioner William Mackay founded the Boys Clubs to keep young boys off the street and combat rising juvenile delinquency in Sydney. The NSW police believed that through sports such as boxing, wrestling and gymnastics, it could teach young boys the principles of citizenship and good work ethic. The Police Boys Clubs were fast growing and continued to play an important role in local communities up until our present day, now the Police Citizen’s Youth Club and with 66 clubs still active across Australian states in 2022.

Although the main objective of PCYC can be situated in a type of community-based welfare work, it is clear there was a keen focus on sporting success across the clubs. PCYC established interclub championships, hosted international sporting events and celebrated members who went on to represent Australia at both a national, international, and Olympic level. The memorialisation of the clubs sporting legacies and its sporting heroes plays an important role in maintaining connections across the clubs and reinforces the cultural value of PCYC to Australian sporting life.

Memory and the PCYC

This process of remembering the clubs’ sporting heritage has also been used for social and political reasons. In November 2023, it was announced that the historic North Sydney PCYC was to be replaced with a new ambulance station. The closure of the club was reported as a ‘blow’ and ‘devastating’ to the local community, which had been in operation since 1953. In an attempt to save the building, members lobbied to the local council through petitions and letters that drew upon the sporting heroes who had trained there such as rugby league star Mario Fenech and boxing champion Kostya Tszyu. The memory of these sporting heroes not only underscored the buildings historical and cultural importance but became a powerful rhetoric in generating public support for saving the club.

This process of remembering the legacies of its past has been reproduced throughout PCYC’s long history. In the 1980s for example, despite the clubs success, the NSW police came under significant criticism for their involvement in the clubs. The Lusher Report argued the involvement of on duty police officers within the organisation, amidst allegations of misconduct and inappropriate use of club funds. As a result of these findings, there was a complete structural overhaul of the organisation’s administration, including a decrease in police involvement and the appointment of governmental officials to the board of directors.

This political shift received significant backlash from both previous and current members who had direct experience with the clubs. Many community members felt that the reforms would affect young peoples’ sporting future, particularly the working class boys who trained at PCYC. In response, communities members intrinsically linked to the clubs drew upon the legacies of its past to make a claim about preserving specific traditions and values throughout the clubs. Peter Anderson, a member of the Legislative Assembly, argued against the reforms, stating he was proud of the clubs history. Anderson, who described himself as a working class boy from Bondi Junction and joined the Eastern Suburbs Boy’s Club at a young age, recounted the sporting champions such as boxers Jimmy Carruthers and Tony Madigan who trained at PCYC and went on to become national champions. Similarly, outside of the political debates previous members wrote into newspapers detailing the heritage and legacies of national heroes who had trained at PCYC. Robin Trotter suggests that this process of remembering fosters images of the past that may promise a sense of security to counter anxieties in the midst of rapid political and social change.(1)

However, in the case of PCYC, it is clear that this mobilisation of its past is often reactionary. In the face of clubs closing, lack of funding and privatisation, PCYC and its communities will draw upon its legacy and its history to make a claim about preserving its future.

(1): Robin Trotter, ‘Nostalgia and the Construction of an Australian Dreaming’, Journal of Australian Studies 23 (1999): 2. Available online