Sydney’s Nineteenth Century Gymnasium Network

Part 1

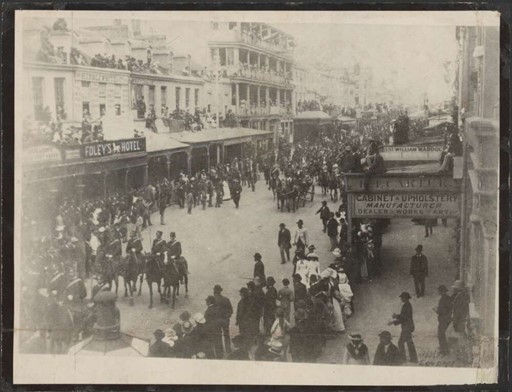

I have lived in Sydney all my life, thinking that I knew the CBD, and its history pretty well. I now realise that there is more to Sydney that lies beneath the foundations of modern offices and even its’ heritage buildings. The moment of rediscovery came from researching the history of gymnasiums featured among the businesses in the Sands Postal Directory; a nineteenth-century ‘white pages’ that circulated in Sydney between 1858 and 1933.

As part of my research internship with Professor Tanya Evans, I have made a database combining articles from the Sands Postal Directory and newspaper articles from Trove to rediscover and reconnect a once active community of the gymnasiums, providing Sydney with recreation, health, and entertainment. This blog will have two parts; first I want to begin by discussing how I conducted my research and explore how early gym culture was understood during the late nineteenth century. Part two will provide an outline of four gymnasiums and a description of their owners from the data I extracted from the Sands Postal Directory and Trove.

What was research like?

The research was not easy, and it wasn’t meant to be. I began in early August sifting through the Sands Postal Directory provided by The City of Sydney Archive. This was easy because the digitised documents were all open access. The first gymnasium appeared in 1869 and the directory only had two hundred pages, however, once I reached the 1880s, the directory became larger with more than one thousand pages. Pretty soon I became friends with Ctrl+F.

I made sure to be cautious about entering names and addresses into Zotero, and always cross-referencing with other articles to confirm that I was collecting the correct data on both the gymnasiums and their owners. I used a different approach with Trove, I downloaded the newspaper articles and sorted them into folders based on the owner. I made sure to stay alert for any typos and used key terms to focus my search results.

Entering the information into Zotero was simple at first, I was very familiar with its layout from previous cataloguing experience, and after three hundred and one entries, at least one thousand reference tags I finally had my database. Then came a system error that repeated the reference tags for at least fifty entries, which meant spending more time reorganising the articles and reallocating the correct tags. I made the choice to finally see my optometrist, and order a pair of reading glasses, a reminder of the physical, as well as the psychological toll that data collection can have on a researcher. Take breaks; if your eyes hurt, seek a medical professional.

After all of that, I now have a database that I know can provide researchers with the information to start exploring the gymnasiums, the owners and the networking that happened in Sydney. What made an impression on me while conducting the research was that these individuals were once well known for providing Sydney with its entertainment, recreation, and health, and yet there’s a lack of recognition. Hence, this is where I come in. Hopefully, my small contribution in the form of my Zotero database can begin to open an avenue for these gymnasiums, their owners, and their stories to be memorialised and reintegrated back into Sydney’s history.

What were the nineteenth-century gymnasiums like?

I must admit, I’m not someone that goes to the gym. The last time I was in a gymnasium was in high school, but I do remember the emphasis on physical education and health, and this approach is not too dissimilar to the gymnasiums of the nineteenth century.

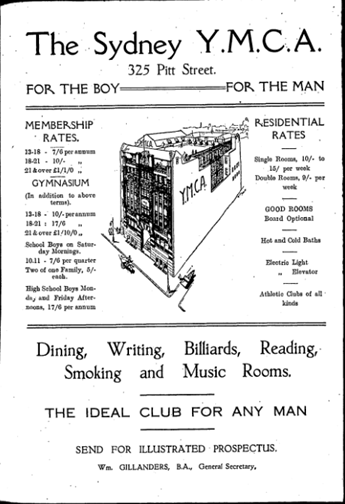

After the Great War, competitive recreation and fitness for men encouraged masculinity to reach its ‘perfection as normality’, steeping the gymnasium with eugenics and mythology for Australians to mimic the Classical Greek athletes (Carden-Coyne 1999, 145). Having the gymnasium made accessible to men of all ages, and classless, the ‘modern classicism’ that provided both a utopic and exclusionary ideal to these venues undermined this equality or ‘democratisation’ that made the gymnasium accessible to all men (Carden-Coyne 1999, 145 - 146). By contrast, the Y.M.C.A. provided gymnasiums for a varying array of recreation activities for men and boys less focused on unrealistic physiques, such as fencing, billiards and smoking; the Y.M.C.A. was a gymnasium branded as an ‘ideal club for any man’ as featured below (Sands Postal Directory 1916).

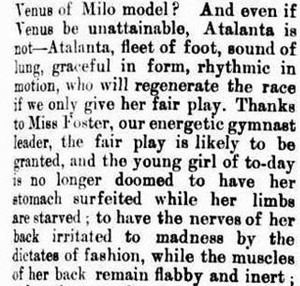

For women, the primary model for Western physical education during the nineteenth century was adopted from the Swedish Gymnastics Movement; its one-sex model focused on the benefits of physical activities towards the development of women of all ages (Westberg 2018, 263). The ladies’ gymnasium at first seemed liberating, with young girls and women having the opportunity to openly participate in physical activities, however, the ideals of ‘Greek womanhood’ became the impetus for encouraging the aims of female fitness (Sands Postal Directory 1889). This was by no means subtle. A journalist described the Australian ‘missy’ as more advanced than her Spartan or Athenian counterparts. She had a responsibility to produce a race of Venus de Milo’s, or at the least be like the athletic Atalanta (Illustrated Sydney News 1889). The journalist goes on to mention:

The gymnasium was a centre for the transformation of one’s self-identity underpinned by both the mythology and unrealistic European ideals about the masculine and feminine physique. The gym was also a democratic space where it was expected that all men could collectively partake in recreation free from one’s class background. However, when physical prowess is introduced into this space it becomes exclusionary in favour of particular forms of athleticism such as wrestling, boxing and bodybuilding (Carden-Coyne 1999, 138).

Find out more about the Sydney gymnasium and its owners in (Part 2) (along with bibliography).