In this piece, Ashok muses about public history and the philosophies of Aboriginal peoples, their intersections, and our connection to the universe.

“Fish out of Water?” My Research in Public History

One may well ask what is a BPhil/MRes philosophy major, planning to write a thesis in the philosophy of mind and metaphysics, doing in public history? I certainly asked myself the same question when I first started my PACE MRes7004 research internship with the AAPHN. I was the proverbial fish out of water. Perhaps it’s not easy to realise that as historians, there’s an implicit kind of understanding for how things are done which non-historians may not be privy to. Be that as it may, gradually I found a way to eke out a place for my philosophical interests and abilities within the public history fold and engage in research I firmly believe worthwhile.

My philosophy thesis intends to argue that consciousness is not derivative nor secondary to nature, as construed by our predominant natural scientific worldview, but fundamental and integral to it. As with history, I have no background in Indigenous Studies, but the little exposure I did have through anthropology and geography units was enough to spark philosophical curiosity and interest, because a similar kind of metaphysical idea seemed to pervade Australian Indigenous peoples’ worldviews. Exploring in this direction, I found an interesting paper by Stephen Muecke (2011: 2) ‘Australian Indigenous Philosophy’, in which he argues that while there is interest in Australian Aboriginal peoples’ knowledge among anthropologists and historians, the philosophy department remains off limits. A perfect example of this can be found in A companion to philosophy in Australia & New Zealand, in which the entry for ‘Australian Aboriginal Philosophy’ proclaims that a “rudimentary philosophy might be constructed” from its body of myths (Charlesworth 2014: 67). So it was that my project for the AAPHN came about, ‘Australian Aboriginal Worldviews: is an Australian Aboriginal philosophy possible?’

Still, one might press, how is this a public history project? One of the aims of the AAPHN, I learnt, as I familiarised myself with the network, is advocacy. And if an Aboriginal peoples’ philosophy is indeed possible, like one day being able to crack open “a volume of “Pitjantjatjarra Philosophy”” (Muecke 2011: 2), then advocating for its acceptance and establishment, backed up by research both historical and philosophical, falls within its remit. In the process of my bibliographic research on this issue, two aspects emerged as frequently recurrent themes. First, while a lot of progress has been made to raise awareness and respect for Australia’s Indigenous peoples and their cultures, this has not yet translated into an appreciation for Aboriginal peoples’ knowledge. That is, knowledge every bit as consequential and applicable to the world as the natural sciences, and thus taken seriously as philosophy by philosophers, and indeed scientists. Second and relatedly, in terms of Australia’s public psyche there appears to be a great lacuna when it comes to genuinely appreciating the philosophical depth that Australian Aboriginal peoples’ traditions of knowledge entail.

Despite the two factors which stand as obstacles to its realisation, what I found was that Aboriginal peoples’ philosophies are not just possible, but already happening. A recent example of which would be Tyson Yungkaporta’s (2019) book Sand Talk: How Indigenous thinking can save the world, founded upon Indigenous knowledge that is codified, so to speak, in the ‘Dreaming’. The ‘Dreaming’ being an approximate umbrella term for the collective and intricate worldviews of Australian Aboriginal peoples. As a work of philosophy, it is a metaphysical and epistemic approach to reality, through which Yungakporta conducts an incisive and challenging analysis of the modern world, and, as he compellingly argues, its problematic metaphysical underpinnings.

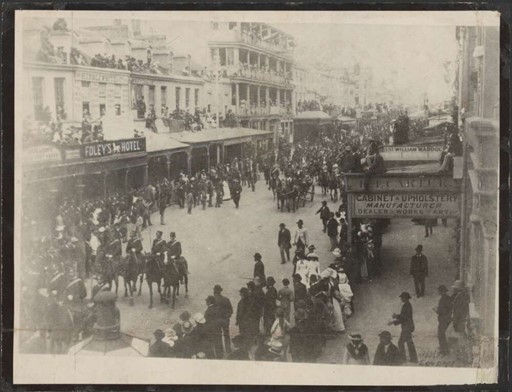

To place this within a historical context, despite the stereotype of Australia as a harsh and inhospitable continent, Gammage’s (2005) work, such as ‘Gardens without fences? Landscape in Aboriginal Australia’ and Bruce Pascoe’s (2017) book Dark Emu: Aboriginal Australia and the Birth of Agriculture, examine remaining evidence of what the lands of Australia were like prior to colonial times. Their research suggesting that it was intricately cultivated and managed to the extent that the landscape appeared to early colonials like a garden or park, providing ample sustenance for Indigenous populations, well beyond the entrenched image of mere hand to mouth subsistence. Yet upon colonial dispossession and dislocation of Aboriginal communities, with their intimate relation to country severed and their knowledge ignored, the ecological balance that had been maintained for millennia rapidly and catastrophically collapsed, precipitating the recurrence of events like extreme bush fires (Broome 2013, Pascoe 2018). One could easily look upon this scenario as a tragic allegorical tale about a clash of worldviews between modernity, which assumes for itself the central position as arbiter of knowledge about the world, and the Dreaming of the Aboriginal peoples, which modernity regards as simply myth and superstition. Except that we are still living it now.

As a public history project, then, part of advocating for the establishment of Australian Aboriginal philosophy is fostering public recognition that the Dreaming is not simply a set of cultural myths to be dutifully respected. Nor is Aboriginal connection to country something that warrants only token acknowledgement. Rather it is an entire paradigm of knowledge and understanding, with a sophisticated phenomenological and metaphysical picture of reality. One that can be applied to the complex challenges we face today, both social and environmental, by research led by Indigenous peoples. Unlike the natural scientific worldview that is the bedrock of modernity, casting us as by-product of a fundamentally inert and mechanistic nature, it is a picture of a living cosmos within which we actively belong.

References and Resources

Broome, R 2013, ‘The great Australian transformation: An argument about our past and its history’, Agora, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 16–24.

Charlesworth, M 2014, ‘Australian Aboriginal Philosophy’, in GR Oppy, N Trakakis, L Burns, S Gardner & F Leigh (eds), A companion to philosophy in Australia & New Zealand,2nd ed., Monash University Publishing, Clayton, Vic, pp. 67–68.

Gammage, B 2005, ‘Gardens without fences? Landscape in Aboriginal Australia – AHR’, Australian Humanities Review, vol. 36, pp. 1–7.

Muecke, S 2011, ‘Australian Indigenous Philosophy’, CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, vol. 13, no. 2.

Pascoe, B 2018, Dark Emu: Aboriginal Australia and the Birth of Agriculture, Magabala Books, Broome, Western Australia.

Roberts, Z, Carlson, B, O’Sullivan, S, Day, M, Rey, J, Kennedy, T, Bakic, T, & Farrell, A. 2021, A guide to writing and speaking about Indigenous People in Australia, Macquarie University.

Yunkaporta, T 2019, Sand talk: how Indigenous thinking can save the world, Text Publishing, Melbourne, Victoria.

We at the AAPHN acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land upon which we work, the Wallamattagal people of the Dharug nation, whose cultures and customs have nurtured, and continue to nurture, this land, since the Dreamtime. We pay our respects to the Dharug people and the Wallamattagal clan. We also acknowledge the Elders of the Dharug nation, past, present and future, and pay our respects to them.

All content on the blog is distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).