Mary Rattigan

Here, Amanda Midlam recounts the tumultuous and interesting life of Mary Rattigan, an Irish migrant to Australia. This work is a product of her PACE internship with the Macquarie University Centre for Applied History and the Irish Famine Memorial.

Introduction

Unfortunately there are no photos of Mary Rattigan. This means we may never know what she looked like but, by delving into the past, we can build a picture of the life of this remarkable woman who showed such spirit and resilience. Generations later, her family still remember her and are inspired by her - and her name is etched in the glass panel of the Irish Famine Memorial at Hyde Park Barracks. It is important that Mary is remembered because Australia was built by women like her, whose contributions are all too often forgotten (see https://irishfaminememorial.org/).

The bare facts of Mary Rattigan’s life are bleak. She was born in Ballymahon, County Longford, actual date unknown but around 1831, and by the age of 18 she had endured unimaginable hardship and had set out to the other side of the world. She had survived famine and the death of both her parents and had been put into a workhouse where the conditions were appalling, after which she left Ireland, under the Earl Grey Scheme, to emigrate to Australia to fend for herself, having no relatives in the colony.

Earl Grey, the British Secretary of State for the colonies, came up with the scheme to address both the shortage of domestic labour and the shortage of females in Australia and also alleviate the overcrowding in Ireland’s workhouses, overflowing due to famine. Under the scheme, 4175 young girls arrived in Australia from Irish workhouses between October 1848 and August 1850. Mary was only one of them but was probably typical. Here are more details about her extraordinary life beginning with some background on where she came from.

Life

Ballymahon, County Longford, Ireland

Mary grew up in Ballymahon. According to John Christopher Farrell, a current Longford resident with an interest in local history, Ballymahon was a small market town that developed as a settlement based around a castle built by the O’Farrell clan and a corn mill on the banks of the River Inny, which forms part of the boundary between County Longford and County Westmeath.

“The economy in the 1800s was totally agricultural with cattle, sheep, pigs and horses the main livestock. Crops grown included potatoes, oats, barley and wheat as well as flax for a declining linen industry. The land was farmed by tenant farmers who held small holdings of between 2 and 10 acres. The tenants were largely Roman Catholic (over 90%) while the landowners were almost exclusively Church of Ireland, Protestant. From 1815 until the famine in 1845, almost half the population lived at subsistence level, just barely surviving year to year.”

Mary’s own direct descendant, Chris Davey, has been intrigued by Mary Rattigan for over forty years and made a trip to Ireland to Ballymahon in County Longford, in search of information about Mary and her family. The local Catholic priest let her look through the original church registers that are written in Latin but the visit was not entirely fruitful.

Mary had tragically lost both parents and, as families were large, possibly siblings as well but Chris notes, “Mary’s parents may have been placed in an unmarked grave due to the numbers of deaths from the famine. I found many Rattigan graves in Ballymahon but not of Mary and Thomas and not of the Famine years”.

John Christopher Farrell points out that it wasn’t just starvation that killed people at the time, “There were many diseases - TB, cholera, measles, whooping cough, and polio among others”.

He gave a blunt description of Ballymahon in the 1840s - “A tough life, but many lives were very harsh back then. Still people were resilient, and simple things gave great pleasure. Family most important, then storytelling and music. Great community spirit where people looked out for each other”.

After her parents died, Mary was placed in the much feared workhouse which was regarded as a shelter of last resort. Food in the Irish workhouses was meagre. Breakfast at 6am was a kind of stirabout porridge, dinner at noon a kind of oatmeal soup occasionally with meat, and usually there was no supper but sometimes there was bread and milk at 6pm.

Fiona Slevin has a PhD in history and has done a lot of work on the famine and its aftermath on small rural towns in Ireland. She notes that on 19 May 1847, in a letter to Paul Cullen, rector of the Irish College in Rome, Bishop O’Higgins of Ardagh described the desperate conditions in his diocese:

“Of course, you have some idea from the papers of the state of the poor of Ireland. Never was any part of the globe visited with so prostrating destitution. It would sicken your heart to see those of our people who, up to this, have escaped death. Persons of twenty years of age appear to be bending under old age, and, in many instances, are become shameless and idiotic from want of every kind.” Slevin, Fiona https://loughrynn.net/great-famine-in-leitrim accessed Nov 2021.

We do not know if Mary was one of the young ones who appeared to be bending under old age but we can be sure that the famine girls who migrated to Australia were tiny due to malnutrition. We also don’t know how many deaths she witnessed both before going into the workhouse and after and the hardship and horror is unimaginable to people of our time. Bishop O’Higgins continued:

“This Diocese is composed of portions of seven counties: Longford, Leitrim, Roscommon, Sligo, King’s County, Cavan, and County Meath. We thus, of necessity, participate most deeply in all the wretchedness of the country. All our proprietors, with scarcely any exception, are absentees; and our condition is truly forlorn. We have in this Diocese five poor houses, and the average deaths in the week are beyond 100 persons in each.” Slevin, Fiona https://loughrynn.net/great-famine-in-leitrim accessed Nov 2021.

There is no doubt Mary would not have been able to see a possible future if she stayed in Ireland, apart from one of desperation and starvation. Chris Davey believes Mary agreed to be selected for the Earl Grey Scheme to escape the workhouse; the unknown future, perhaps, being preferable to the known. To be selected girls had to be young, healthy, single, obedient and free of smallpox, so she hopes Mary’s physical condition was not dire. Before leaving Ireland, Mary was given a regulation kit of clothing, linen and utensils stored in a lockable box and a Douay Bible. She had probably previously never owned so many possessions.

Chris Davey believes it was clear to the workhouse orphan girls that they would never return to Ireland. Mary must have had fortitude to emigrate knowing that ahead of her she had the challenge of forging a life for herself. These days refugees still come to Australia for a better life and for some of them their experiences parallel Mary’s: trauma and grief at an early age, followed by a long sea voyage. In fact in recognition of this the Irish Famine Memorial Fund has programs supporting refugees (see https://irishfaminememorial.org/programs/).

We know from the Earl Grey Scheme records that she was one of fifty girls migrating from Longford. She was discharged from her workhouse and was taken by horse and cart to Dublin, her port of embarkation in Ireland. From there she travelled by ship to England, perhaps sailing directly to Plymouth, or perhaps she arrived in England at another port and then travelled to Plymouth, where she boarded the Digby for the long voyage to Australia. Recorded as still in her teens, Roman Catholic, able to read but not able to write and both her parents dead, Mary headed off to a new land and unknown life.

The Journey to Australia

Most people did not travel much then, nor far from home generally, but due to the circumstances in Ireland Mary would have known of people emigrating - leaving for America, England, Scotland, Canada and Australia plus, of course, she would have known that for many years the English had been sending Irish political prisoners to Australia.

John Christopher Farrell enlightened me about travel for Longford residents in those days. “Most people lived their lives in the local area. The army would have given men travel opportunities but, apart from that, agricultural labourers would work in their local area, perhaps going to the local town fair a few times a year. Women were more likely to be more limited in travel, perhaps to town but only 2 or 3 times a year.”

Mary, however, was a domestic servant and if she worked in one of the bigger houses it is possible she may have travelled with her employers but, as she came from a landlocked county, it is likely that she would never have seen the sea before travelling to England. We will never know whether in her heart Mary wanted to go, to leave the misery and starvation behind; or if she felt she had no real choice with conditions at home being so bad and the promise of an indentured job in Australia. Either way, she would have little knowledge about what she was going to but she would have known that the sea voyage would take some months. It must have been terrifying and we can only hope she enjoyed the company of the other girls, didn’t suffer seasickness and perhaps felt optimism for a better life.

Mary left Plymouth on the 16th of December 1848, sailing on the Digby. Her name on the Immigrant List for that ship gives her age as 18; her occupation as house servant; her native place as Ballymahon, Co. Longford; her religion as Catholic and also the information that she could read. Irish was rarely written at the time so the ability to read indicates she knew some English but it is important to remember that Irish would have been her native language. Mary was heading to a colony run by the people who oppressed Ireland, looked down on the Irish and spoke a different language.

The amount of food she was fed on board must have amazed her after living in a state of starvation for some years. The ration was half a pound of beef or pork a day and the girls would have gained condition on board. The voyages that took place under the Earl Grey Scheme were generally well run, with only one death out of the more than 4000 girls who emigrated. On each ship there was a surgeon to look after the girls’ health, a school mistress and a religious instructor. Mary did not list a complaint while on board the ship but another girl, Catherine Hartigan, complained about the ship’s master physically assaulting her.

Australia

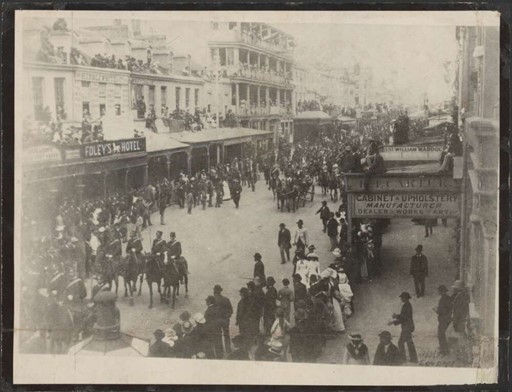

Mary arrived in Sydney on the 4th of April 1849 and with more than 200 other girls from the Digby was taken to the Hyde Park Barracks. This is where she was housed until sent to an indentured job and is where her name is now etched into the Irish Famine Memorial. She would have found out quickly that it was not a great time to arrive in the colony. There was a drought inland, the economy was in depression and the settlement was rocked by corruption scandals. She would also have been aware of the racism towards the Irish. Newspaper reports show that many people of English origin believed the Irish to be dirty and lazy. No education was offered to her and Mary’s days were occupied by jobs given to her before she was sent to Parramatta to work for the overseer of the Parramatta Hospital. But it wasn’t long before she ran into trouble.

The Sydney Morning Herald of 12 Feb 1850 reported that Mary Rhattacan (sic) was charged with being indolent and impertinent and returned to Barracks.

We do not know if the loss of this position was a cause of regret for her. Chris Davey writes, “From all of these ordeals she must have been desperately downtrodden and frightened yet she is dismissed from her first position at Parramatta Hospital, or the overseer’s residence, due to indolence and impertinence. What was her treatment by Williams or his wife or others to her? The above ordeals either didn’t break her character or they helped form it!”.

Unfortunately the records do not include her side of the story. We understand now that she must have been traumatised by all she had endured and witnessed but we don’t know if she regretted losing her indentureship and the small income it gave her. She was sent back to one of the Sydney work houses.

It wasn’t long before the Earl Grey scheme ended due to opposition from colonists. According to historian, Trevor McClaughlin, the colonial press described the girls as ignorant Irish, untrained and immoral. They were Catholics suspected of being sent to Romanise the colonies. In April 1850, the last orphan ship, the Tippoo Saib, left Plymouth. By that time, Mary’s life had been uprooted once by emigrating and it was about to be uprooted again by leaving the major settlement. She was sent to Twofold Bay with seven other girls. The ship on which they sailed was called “The Shamrock” and its date of departure from Sydney was the 2nd of May 1850 and Mary soon found herself in Boydtown on the shores of Twofold Bay.

Twofold Bay

Despite its name Boydtown was not a town and still isn’t, having a population of only 70 in the 2016 census. In the official census of 1849, the year before Mary’s arrival, the population of Boydtown was bigger and stood at 200, however operations ceased and Boydtown was virtually abandoned by May 1850 when Mary arrived. She must have felt for the second time that she had travelled to the end of the earth.

The history behind Boydtown is that it was a private settlement owned by Ben Boyd who is often described as an entrepreneur which is a euphemism for fraudster. He was a ruthless man and a narcissist who founded a privately owned town, named after himself, that he wanted to become the capital of the colony. His money seemed endless but his luck ran out. It was investors’ money that he spent as if it was his own as he developed Boydtown and bought up massive amounts of land, becoming one of the major land holders in NSW. After being in Australia for only about 7 years, he skipped out in October 1849, owing a fortune and leaving Boydtown without money and without support. Tom Mead, historian and novelist, claims he left debts of over £400,000, a financial scandal that rocked Sydney. In Twofold Bay, Boyd’s name was mud. He owed his workers money.

Boydtown is situated on the beach and Mary would have been able to see the government settlement of Eden across the water, a small township on the promontory that juts into Twofold Bay, but she probably did not get there often. The drive from Eden to Boydtown on the western shore of the bay is now only 8 kilometres but in Mary’s day travel between the two settlements would most likely have meant rowing across the water. She must have felt marooned.

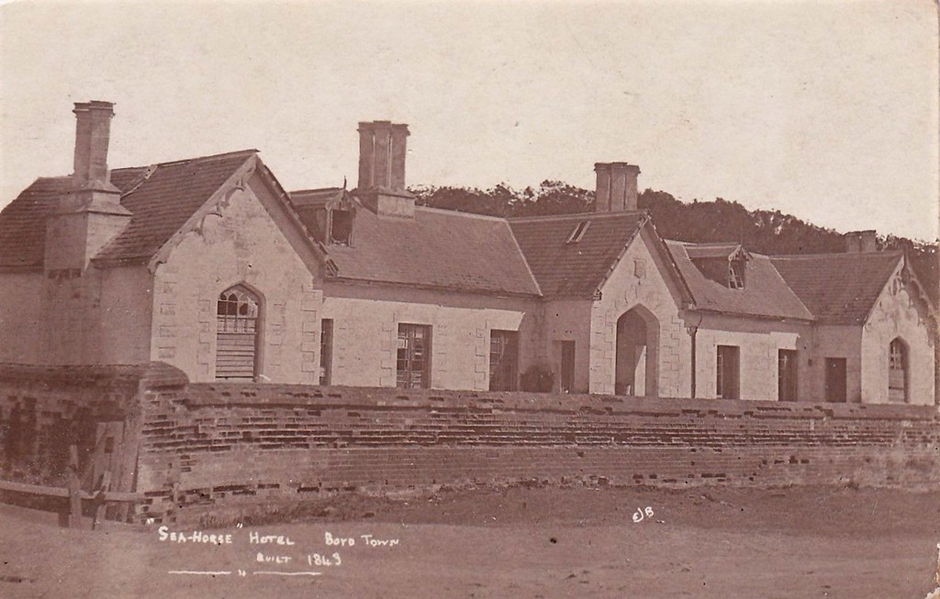

The population of Eden in 1850 was only 49 but when gold was discovered inland in 1852 and then a bigger find at Kiandra in 1859, the seaport of Eden became a lot busier and people arrived by ship to trek to the gold fields. At Boydtown there were buildings, the impressive Seahorse Inn, which is still standing, a church nearby on a hill, still standing but crumbling plus warehouses, workmen’s cottages and the stinking works where sheep were rendered down as the bottom had dropped out of wool prices. But the owner had vanished, the vision and the money that supported it had ended abruptly, and as government services in the region were established they went to Eden, not Boydtown.

Too many pioneer stories leave out the original inhabitants of the locality. Pioneer stories are told as if the original people had somehow “gone” before white settlers arrived or else information about Aboriginal people is mentioned, but only briefly as if the story of a place only really begins with the arrival of white settlers. This story looks deeper. Mary Rattigan found herself living on Thaua country that had been renamed Boydtown less than ten years previously. Thaua people were, and still are, present in the Twofold Bay area.

The white history of the district began in 1798 when George Bass and Matthew Flinders surveyed Twofold Bay. They named the small harbour in Eden, Snug Cove, and Flinders noted an encounter with locals in his journal, A Voyage to Terra Australis:

In the way from Snug Cove, through the wood, to the long northern beach, where I proposed to measure a base line, our attention was suddenly called by the screams of three women, who took up their children and ran off in great consternation. Soon afterward a man made his appearance. He was of a middle age, unarmed, except with a whaddie, or wooden scimitar, and came up to us seemingly with careless confidence. We made much of him, and gave him some biscuit; and he in return presented us with a piece of gristly fat, probably of whale. This I tasted; but watching an opportunity to spit it out when he should not be looking, I perceived him doing precisely the same thing with our biscuit, whose taste was probably no more agreeable to him, than his whale was to me. Walking onward with us to the long beach, our new acquaintance picked up from the grass a long wooden spear, pointed with bone; but this he hid a little further on, making signs that he should take it on his return. The commencement of our trigonometrical operations was seen by him with indifference, if not contempt; and he quitted us, apparently satisfied that, from people who could thus occupy themselves seriously, there was nothing to be apprehended.

An elder, Uncle Ossie Cruse, explained to me that the traditional diet was very healthy except it lacked fat. Local people had readily available and plentiful protein and plant foods but the animals, birds and fish they ate had very little fat. Twice a year there were festivals, the bogong moth festival up in the mountains and the whale festival on the coast where people had their fill of fat and in the case of whales could preserve it. Perhaps the man on the beach assumed Flinders lacked fat in his diet and so offered him the blubber.

This first encounter between black and white in Twofold Bay was peaceful, but after Bass and Flinders came sealers of different nationalities who made trips to the far south coast, which lay beyond the reach of white law. According to historian Mark McKenna, Twofold Bay was a rough frontier for around forty years. The sealers did not come to settle but came to raid resources and did not care about conditions in the district or what damage they did. After the sealers came whalers, with the first whaling station starting operations in 1828 and, as there was a lucrative market for whale oil, soon there were whaling stations dotted around the bay. Some of the whalers brought their families with them and settled permanently, bringing with them the desire to establish their idea of ‘white civilisation’.

Middens in the vicinity prove many thousands of years of prior occupation but by the time Mary arrived, in May 1850, pastoralists had taken the land and white whalers employed Aboriginal crews. The Thaua people had traditionally had everything they needed in their local environment, not just for sustenance, but for deeply satisfying lives, however the white settlers needed money to buy stores, equipment, livestock and everything they needed. At Boydtown there was a company store that charged company prices, but it is not known if it was operating when Mary arrived after Boyd’s departure. Oswald Brierly, an artist, had been Boyd’s manager at Boydtown, looking after his whaling and pastoral interests, before leaving in 1848. Brierly was interested in the local people and befriended and painted a local man, Budginbro.

Steven Holmes, a Thaua man who is directly descended from Budginbro, lives locally and has spearheaded a campaign to change the name of Ben Boyd National Park. He regards Boyd in blunt terms. “My ancestors didn’t just get up and walk away, they’re buried here.” He explains that a lot of his ancestors were chained and kept in pig pens in cold weather. He makes it clear he is hurt by this and is adamant that Boyd’s name should not be memorialised by having a national park named after him.

Steven Holmes does not know of any connection with Mary and unfortunately with neither the original inhabitants nor immigrants such as Mary able to write, we lack records of any interaction. What we do know is that they were both living in the same locality at the same time. What we also know is that both Mary and the original occupants had lived through sustained trauma. Mary, on the one hand, had been told she had a chance at a new and better life, although that chance must have seemed slim to her. On the other hand, for the original people, their traditional way of life disintegrating must have been devastating and with their land being taken their new lives could not have looked promising.

The Thaua had plentiful food sources in their natural environment – animals, plants, fish and shellfish including abalone, oysters and bimbulas (cockles). In Mary’s experience food came from hard work on a farm owned by someone else – crops and livestock such as potatoes, barley, oats and pigs. The settlers from the far off northern hemisphere often didn’t recognise resources such as foods and medicines that locals had used for millennia but both the newcomers and the original inhabitants needed land. Land occupation and ownership was an issue for both black and white. Sacred and important sites were taken for buildings or farming and fenced off but unlike some other parts of Australia at least on the coast the Thaua still had the means of feeding themselves from the sea.

Motherhood then Marriage

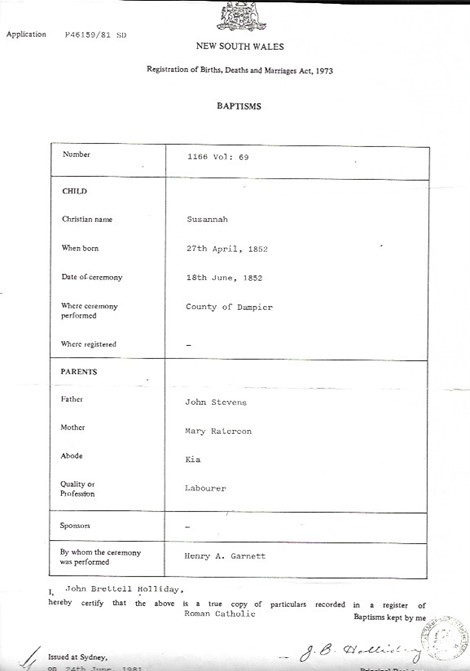

We don’t know how Mary established herself at Twofold Bay but the records show her life changed again when, after two years on the far south coast, she became a mother on 27 April 1852. This child was Susannah, a direct ancestor of Chris Davey. On the birth certificate John Stevens is listed as father. Later she married Thomas Stevens. Was there a John Stevens and if so was he related to the man she went on to marry and spend the rest of her life with? Or was this the same man? There is no John Stevens at the right period on the excellent Monaro Pioneers website and it seems most likely it was a mistake. Mary’s own name was written on the baptism certificate as Ratercon. John Stevens was born in London in 1821, so was about ten years older than Mary and had a different religion from her own and a different native tongue.

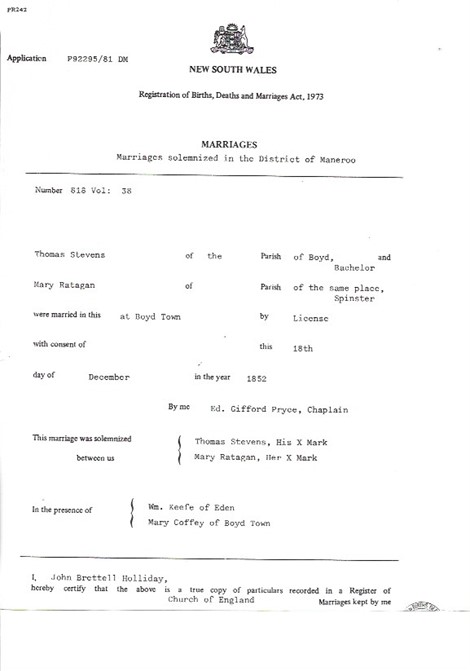

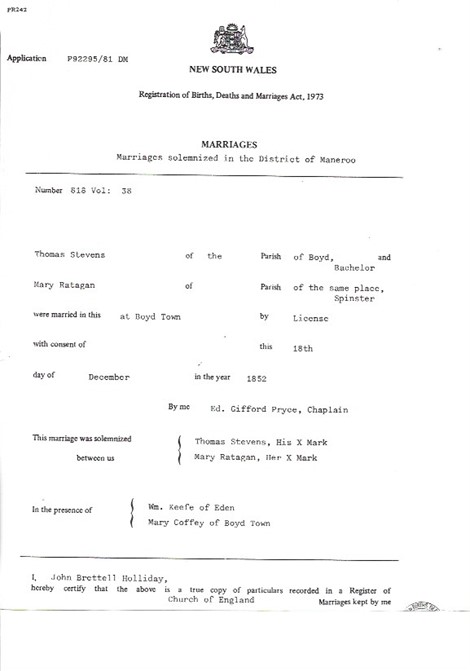

Susannah had a Roman Catholic baptism but on 18 December 1852, Mary Rattigan and Thomas Stevens married at Boydtown in a Church of England ceremony. Had Mary given up her Catholicism or were there practical reasons for a Church of England wedding? Did she believe in God or had her experiences given her doubts? This is something we cannot know.

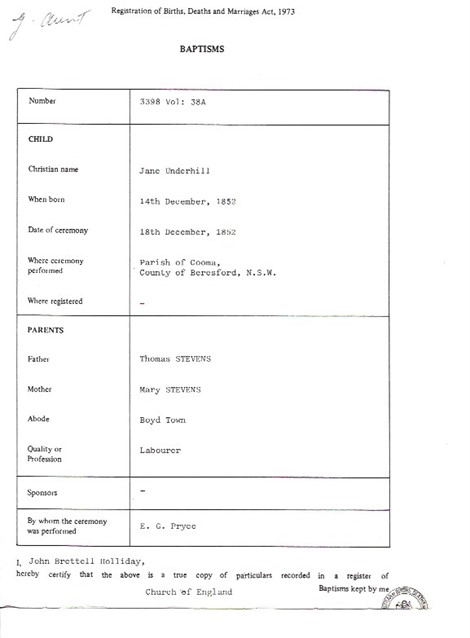

What we do know is that there is a great mystery about Mary’s life at this time. There is a baptism certificate for a second baby, Jane Underhill Stevens, with the same date as their wedding. To add to the mystery the wedding was in coastal Boydtown but Mary and Thomas appear to have been inland up the mountain at Cooma for the baptism of the baby on the same day (See below for both baptism certificates and their marriage certificate).

This second baby, according to the baptism certificate, was reportedly born only four days before, meaning an age difference of only 7.5 months between Susanna and Jane. If the dates are correct, medical advice suggests it is extremely unlikely, if not impossible, for the second baby to have survived. There is also the problem of the geographical distance between Boydtown and Cooma to consider. Connie Stevens, a family member who still lives locally, is adamant. “It would not have been possible in those days. The roads and transport would have made that impossible”.

Perhaps the year of birth for Susannah was recorded wrongly? Or perhaps baby Jane Underhill, the only one of the children to be given a middle name, was adopted although Mary and Thomas Stevens are named as parents. Is the name Underhill a clue? A search reveals there was a Thomas Underhill working for the Imlay brothers in Twofold Bay. He was born in Birmingham and transported to Australia as a convict for stealing clothes at the age of fourteen. He married an Irish woman named Jane Kirkland. At the time baby Jane Underhill was born, Thomas Underhill was married with six children and went on to have seven more with the same wife. Had he helped Mary and Thomas Stevens and been thanked by having the baby named after his wife? Or had his wife, Jane Kirkland Underhill, helped Mary and earned her gratitude? Neither possibility explains the difficulty with the dates. A dark part of me wonders if perhaps Jane Underhill was adopted and Underhill is a clue to her real parentage and I can’t help speculating, if Thomas Underhill was the father, who was the mother?

Anyone could have used the names Mary and Thomas Stevens at the church in Cooma. If Mary adopted this child – and it is a big if - it was an act of supreme love. Mary had no family in the colony apart from her husband. Could the mother have been a friend? I am speculating that friendships, where there was no family support in a new country, would have been enormously important. The mystery intrigues the family and one member suggested DNA testing of descendants to see if that gave any clues but Jane Underhill Stevens had no children.

Land Ownership

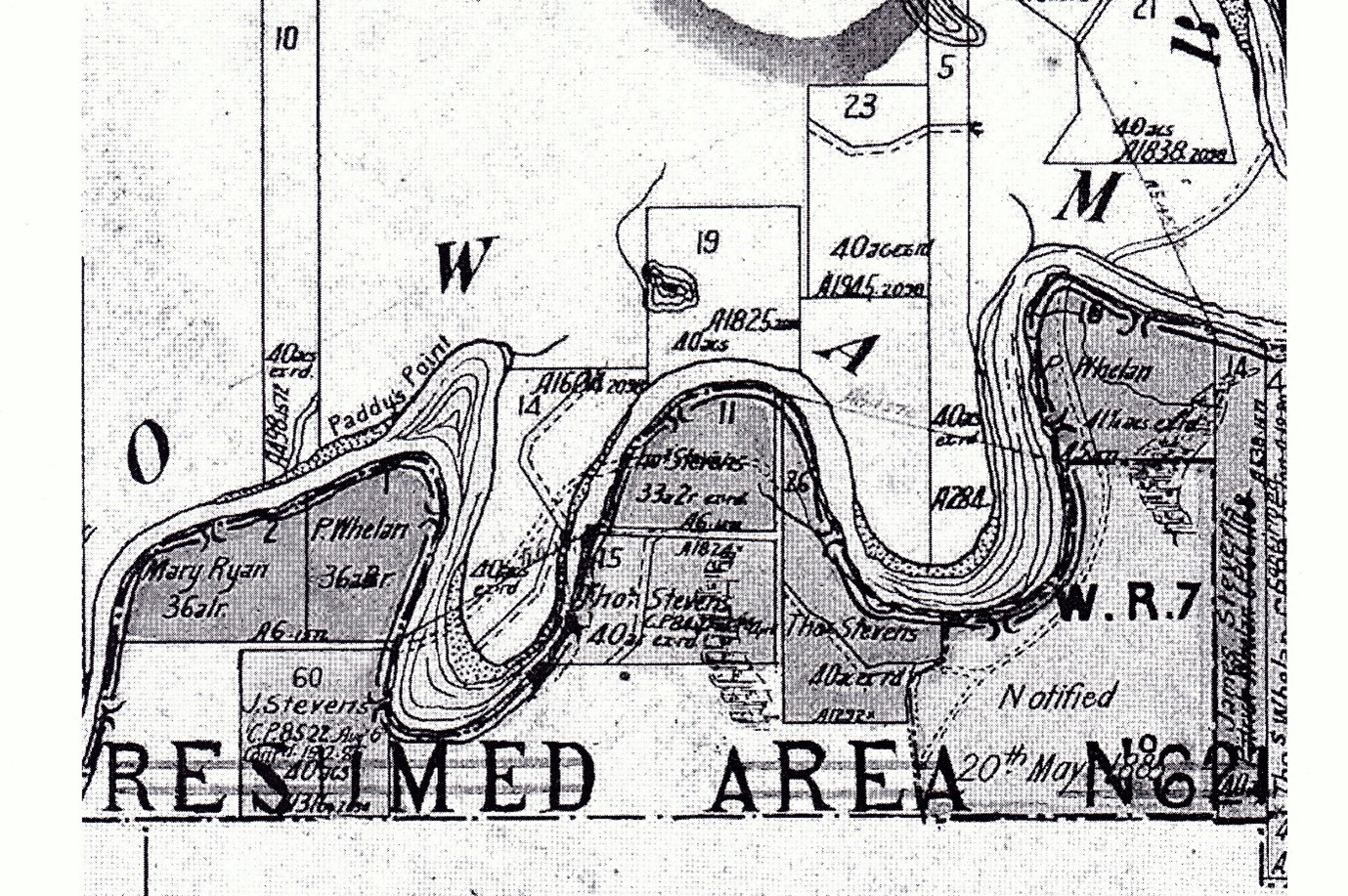

In 1856, there was a massive land sale of suburban lots in the township of Eden and rural lots in surrounding areas. Mary and Thomas managed to buy 33 acres of land on the Kiah River near Boydtown at an auction, on May 2, almost six years to the day since Mary arrived in Twofold Bay. The upset price was £1 per acre, which means that was the lowest price the government would accept at auction and the deposit was ten percent. It is not known what price they actually paid for the land and where they got the money for the deposit but they now owned land on the Kiah River that was about ten times bigger than a leased Irish farm. There was no consent to the sale of land from the traditional owners but it was legal under white law.

By this time Mary and Thomas had three children: Susannah and Jane, born less than a year apart, and then three years after Jane, baby Benjamin arrived. Life would have been very busy with three young children and land to farm but it must have felt like they had really fallen on their feet.

A map, above, shows their land which appears to be part of a small Irish enclave on the river with the Englishman, Thomas Stevens, being the odd one out. The land on both sides of the Stevens was bought at the same sale by Patrick Whelan who had done well for himself. Presumably Paddy’s Point marked on the map was named after him and these days Whelan’s Swamp is nearby. Born in 1804 in County Tipperary, Patrick had been a convict with prisoner’s number 36/1037. He was sentenced at Kings County Ireland on 16 July 1835 to seven years for assault and transported on the ship “Surry”. He arrived in Sydney Australia on 17 May 1836 and was granted a certificate of freedom number on 15 July 1843. Another parcel of land was taken up by Mary Ryan, the mother of Patrick Whelan’s wife, who was also called Mary.

New South Wales Government Gazette, Saturday 15 March 1856, p. 935 (Article available here):

PROCLAMATION: By His Excellency Sir William Thomas Denison, Knight, Governor General in and over all Her Majesty’s Colonies of New South Wales, Tasmania, Victoria, South Australia, and Western. Australia, and Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief of the Territory of New South Wales and its Dependencies, and Vice-Admiral of the same, &c., &c., &c. IN pursuance of the authority in me vested, and in accordance with Hie Regulations of 8th March, 1853, respecting the establishment of Local Land Offices, I do hereby notify and pro claim, that at Eleven o’clock of Friday, the 2nd day of May next, the following Town, Sub urban, and Country Lots of Land will be offered for sale by public auction, at the Police Office, Eden, at the upset price affixed to each lot respectively. (Deposit 10 per cent.)

The government proclamation goes on to state that the parcel of land Mary and Thomas bought was already known as Three Water Holes. Perhaps Thomas and Mary were squatting there before purchasing? There had been a big demand for the government to release land. The Proclamation continues:

- Auckland, 33a. 2r., Thirty-three acres and two roods, parish of Kiah, portion No. 11, commonly called Three Water Holes, Towamba River; commencing at the north-east corner, being a point on the right bank of the Towamba River bearing about west 16 degrees north, and distant 29 chains from the south-west corner of portion No. 10, and bounded on the east by a line bearing south 17 chains; on the south by a line bearing west 22 chains to the Towamba River; and on the west and north by the right bank of the Towamba River downwards to the point of commencement. Upset price £1 per acre.

Two years later, Mary, aged 30, gave birth to Thomas most likely assisted by her neighbour, Mary Ryan, who is described on his birth certificate as a nurse. The Ryan family migrated to Australia as free settlers eight years before Mary Rattigan arrived and they were neighbours at Kiah. Being a nurse was not a formal qualification at the time, but many of the women assisting at births had a lot of knowledge and experience. Certainly there would not have been much choice or access for Mary Stevens to obtain health care for herself and her family. As Chris Davey notes, “The very act that Mary survived to marry, have children and own land is a measure of her success.” (For Thomas’ birth certificate see below).

Friends

Sadly friendships don’t leave government and parish records and there are no known photographs of Mary Rattigan, let alone with friends, but I asked Chris Davey what she thought. She speculated that Mary Rattigan may have been friends with Jane Underhill nee Kirkland, who was born in 1824 and had fourteen children, six by the time Mary gave birth for the first time. Chris writes, “Jane Underhill was only 6 years older than Mary. I like to think Mary had a friend otherwise life would have been more hard and lonely. Imagine being able to speak Gaelic and about Ireland, the Famine, the journey they each undertook. A release for both of them”.

Personally I think, and hope, that our Mary found a good friend in her near neighbour Mary Whelan, nee Ryan. Mary Whelan was born in 1828, so was only two or three years older than our Mary but, by the time Susannah Stevens was born, already had three children and was heavily pregnant with the fourth. Both young women had come from Ireland and settled in Kiah, but Mary Whelan had the luck to have her mother and father at hand. All Chris Davey and I can do is speculate and I could not find more information about friendships, but Gail Gibson from Bega Valley Genealogists gave me a good tip – if you are looking for friends look at the names of witnesses on wedding certificates and the names of godparents on baptism certificates.

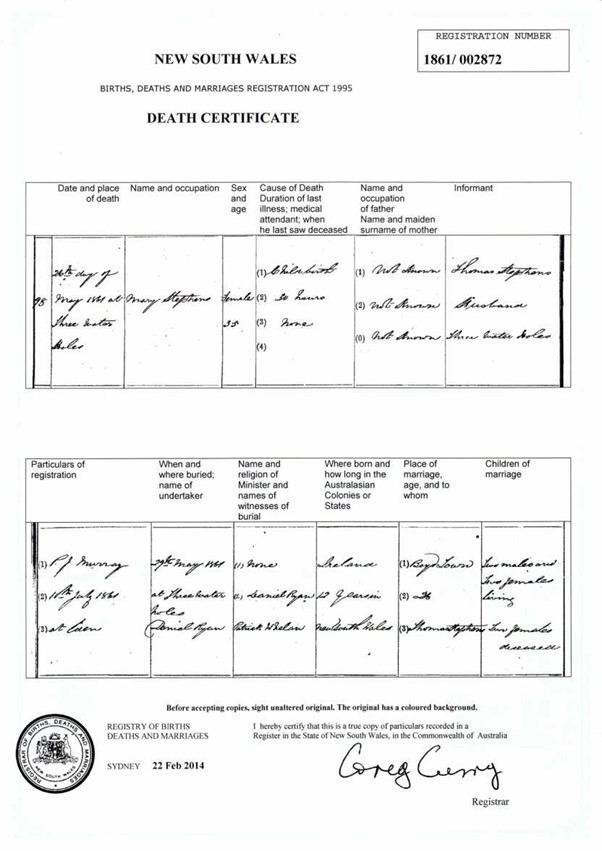

Birth and Death

On the 26 May 1861, Mary died giving birth. She had endured 30 hours of a labour that went dreadfully wrong before she passed away. The baby girl died with her. The river was in flood and no-one could go for help and it was said that the neighbours for miles around could hear her screams as she laboured. Because of the flood and the inability to travel she was buried on the land at Three Water Holes but there is one last mystery in her story. Chris Davey was told by her aunt, Heather Dulihunty, of a further tragedy involving a later flood that washed out the grave. However, Connie Stevens states there is a grave on the land and says she was told by Keith Cross, a local historian with a specialty in burials, that it belonged to Mary Rattigan. Unfortunately both Heather Dulihunty and Keith Cross have passed away so we can’t ask them for more information. Perhaps, like so much else, we will never know more. (For the death certificate, see below)

After Death

Thomas remarried an English woman, Eliza Sutton, just six months after Mary’s death. He would have needed someone to care for the children while he worked the farm but it may well have been a love match. Thomas and Eliza had five children together and stayed married until his death in 1905 and are buried together in Eden cemetery. It is not known if Mary ever knew Eliza Sutton. According to Connie Stevens, a descendent of Thomas and Eliza, they lost the land for failing to make payments but they stayed in the district.

Conclusion

That was it. The short life of Mary Rattigan Stevens was over, much of it lived at the serrated and sharp end of terrible experiences. Mary Rattigan suffered through starvation, death of parents, emigration and isolation. We can only hope she was happy in her marriage and we can be certain that buying land must have been a happy and exciting time. Mary’s life seems so difficult by today’s standards, but not perhaps by the norms of the time. Many people like Mary must have lived and died and left no trace apart from their uncounted descendants - some of the Irish Famine Girls were so small from malnutrition that they could not give birth but others had large families. These young women made a profound contribution to modern Australia. There were over 4000 of them. There must be very many Australians descended from them.

As a postscript Mary Rattigan is to have not just one memorial but two. Her name is etched on the Irish Famine Memorial in Sydney and now the current owner of the land where she lived at Kiah plans to plant a tree on the spot where her grave was believed to be and is creating a memorial for her there.

Lest we forget.

Acknowledgements

This work was completed by Amanda Midlam as part of the course requirement for FOAR7004: Arts Internship for Researchers while she was a MRes student at Macquarie University and supervised by Associate Professor Tanya Evans, Director of the Centre for Applied History.

Many thanks to:

- Trevor McClaughlin whose books, Barefoot and Pregnant? and blog which were indispensable to the writing of “Mary Rattigan’s Life” and “How to Research and Write the Life Stories of Irish Famine Girls”.

- Dr Tanya Evans from Macquarie University for her guidance.

- Chris Davey for her family research.

- Connie Stevens for sharing her family contacts with me.

- Bega Valley Genealogists, especially Gail Gibson, for her research.

- Fiona Slevin for her historical knowledge or Irish towns

- Mark McKenna for his book Looking for Blackfellows Point

- John Christopher Farrell for meeting my request on a Facebook page with such unique and important information and perspectives.

- Irish Famine Memorial without which I would not have undertaken this research.

- Steven Holmes, proud Thaua man, for his connection to Thaua country and the way he advocates for it

If you would like to access any of the resources mentioned please contact us at the AAPHN.

Supplementary resources

Several supplementary resources, including photos of Mary and Thomas, a map of Kiah, and several birth, baptism and death certificates. Rights indicated in image captions.

Bibliography

Personal Contacts

Connie Stevens (member of family of Mary Rattigan)

Gail Gibson (local genealogist)

Angela George (local historian)

Trevor McClaughlin (email)

Trish Power (email)

Codie Thomas (living on property where Mary lived and is buried)

Local history organisations

Bega Valley Genealogists

Eden Killer Whale Museum

Bega Family Museum

Bega Valley Shire Library – local history collection

Monaro Pioneers

Towamba Valley History website

Pambula Historical Society

South Coast History Society

Electronic sources

Bega Valley Notice Board (Facebook)

Bega Valley Notice Board (Nice Group) (Facebook)

Bemboka Notice Board (Facebook)

Eden Remembers (Facebook)

Irish Orphan Famine Girls Descendants Group Australia (Facebook)

McClaughlin, Trevor. Trevor’s blog

Slevin, Fiona at https://loughrynn.net/great-famine-in-leitrim, accessed Nov 2021.

The Eden Voice (Facebook)

We Are the Survivors: Boyle Workhouse (GIFCC March 2019)

Books

Barratt, Shirley. Rush Oh!, Picador, 2015.

Blair, Leonie and McIntyre, Perry. Fair Delinquents. Either Side Publications.

Clery, Kate. The Forgotten Corner Interviews. Eden Killer Whale Museum. 2000

Crowley, John (ed.) Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, Cork University Press, 2012

Diamond, Marion. Ben Boyd of Boydtown, Melbourne University Press, 1995.

Evans, Tanya. “Orphans and Spinsters” in Fractured Families: Life on the Margins in Colonial New South Wales. UNSW Press 2015.

McKenna, Mark. Looking for Blackfellows Point. UNSW. 2014.

McKenzie, J.A.S. The Story of Twofold Bay, Eden Killer Whale Museum and Historical Society.

McClaughlin, Dymphna, “Subsistent Women” in Crowley, John (ed.) Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, Cork University Press, 2012.

McClaughlin, Trevor. Barefoot and Pregnant? Irish Famine Girls in Australia, Vol 1, Genealogical Society of Victoria, 1991.

McClaughlin, Trevor. Barefoot and Pregnant? Irish Famine Girls in Australia, Vol 2. Genealogical Society of Victoria, 2001.

Mead, Tom. Empire of Straw, Dolphin Books. 1994.

Reid, Richard and Morgan, Cheryl. A Decent Set of Girls. Yass Heritage Project. 1996.

Reilly, Terry. Mayo’s Forgotten Famine Girls: from Workhouse to Australia (1848 – 1850) & convict journal [email protected] (GIFFC March 2019 newsletter)

Miscellaneous

Church and civil records of births, deaths and marriages (here and Ireland)

Fairall, Jon. “Women Who Changed Australia” (Tippoo Saib) (GIFCC Oct 2019 newsletter).

GIFCC newsletters

Goulburn Diocese for church records.

Hunter River Steamship Co

Immigration Correspondence

McHugh, Sonia – podcast

Perry’s reading list (mostly context)

Shipping lists inc. Aust shipping 1788-1968 passengers and crew: Available at <www.blaxland.com/ozships/alpha/pass>

Site visits: local places where they lived, worked, died.

Workhouse admission and discharge papers (Ireland).

License All content on the blog is distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).