Public History in the Northern Territory

Public history in the Northern Territory broadly reflects its official history. That is, few other than ‘official’ records exist in the colonial context and they are carefully crafted to avoid, ignore or obfuscate unpleasantries. Unfortunately, unpleasantries abound.

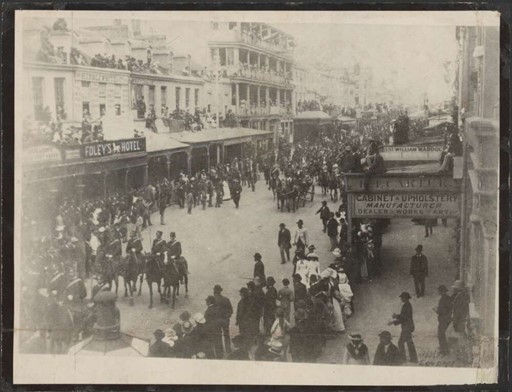

Happily, though, it is public history that has brought these to the fore. It is the case that the Northern Territory was part of the colony of New South Wales until 1863 when it was ceded to South Australia. Few official records exist of the NSW era because there was little activity in this part of the country by colonists until after Stuart crossed from south to north in 1862.

Sadly, the NT was not the panacea South Australia hoped for and by 1907, it was licking its economic wounds and seeking to divest the NT. Ultimately, the Commonwealth relented and in 1911, South Australia officially ceded the NT to the Australian Government.

Few records of that period are available save and except for official reports and the much later writings of police, pastoralists and some early pioneering families. Trove holds newspapers from the time, and they typically reflect colonial views and the quaint social mores of the day. Records do exist, however, in the form of Aboriginal artwork, oral histories, places with historic associations and significance and corroborees, and these deal with the brutal reality of what happened in the Northern Territory. It’s a wholly unappetising story yet its legacy is clearly evident today.

Official records tend to be divided between three repositories: South Australian institutions such as the State Library and State Records Office; the National Archives of Australia; and, to a far more limited extent, the Northern Territory Library and Archives, which was established in 1978 upon the conferral of limited self-government. It is the case, though, that both SA and the Commonwealth have reached agreements with the NT repositories that in-demand records relating to the NT are held either in Darwin or Alice Springs.

For many years, the World War II experience of the NT was untold or largely unknown (as an example, the first Japanese prisoner of war taken on Australian soil was taken by an Aboriginal man on the Tiwi Islands). That period is now arguably the best known of NT history, thanks predominantly to the Federal Government’s Australia Remembers commemoration in 1995. Even so, the vast majority of Australia remains of the view that Darwin was bombed once. A little research will quickly disavow anyone of that notion, never mind if a wider net is cast over northern Australia.

History was not particularly a big-ticket item in school curricula and, in any event, depended upon the expertise of the limited number of teachers who were attracted to the NT under either the Commonwealth or later NT regimes. There was no higher education institution until 1974 when the Darwin Community College, itself predominantly a VET provider, was born, only to be badly damaged by Cyclone Tracy in December of the same year.

Following self-government in 1978, a tortuous wrestling match ensued between the NT and Australian governments, and that resulted in, variously, the Darwin Institute of Technology, the University College of the Northern Territory, the Northern Territory University and—finally—Charles Darwin University, which is named after a man who never came within cooee of the place. Later came the Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education (BIITE). Each of these, at some point, included a history curriculum and, more specifically, Northern Territory history. At the forefront was the late Emeritus Professor Alan Powell who was extremely well written on the chequered and troubled history of the Northern Territory.

Culturally, the NT is eclectic with immigrant histories ranging from Makassan trepangers and Chinese Coolies to Afghan cameleers and almost everything in between. At present, the most in-demand language for interpreting and translation (apart from Aboriginal languages) is Swahili whereas a decade ago it was Indonesian and Somali.

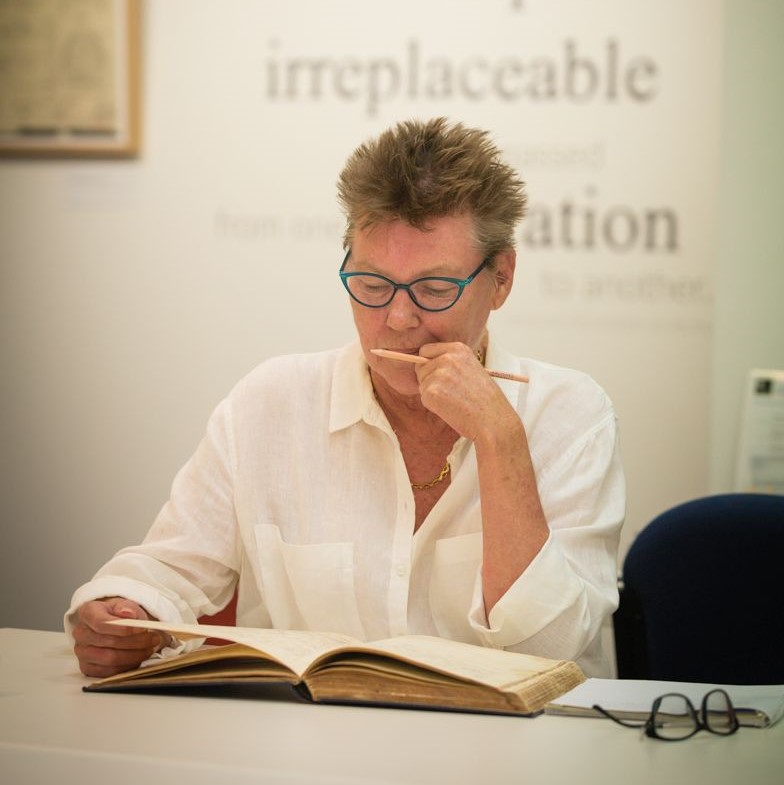

Like other jurisdictions, the NT has a smattering of invaluable local historical societies and museums, the National Trust, a dedicated Heritage Branch within the NT Government apparatus, the Professional Historians Association and a Historical Society of the Northern Territory, the latter of which ambitiously publishes an annual peer-reviewed journal and a modest program of books and occasional papers for an extremely limited market. An oral history program run by the Library and Archives NT has an on-again-off-again existence (always subject to funding) but provides an invaluable research resource for public and professional historians alike. Library and Archives NT also employs some well qualified historians to assist researchers and compile historical resources. It also co-hosts the annual History Colloquium with the Professional Historians Association.

Without doubt, the Northern Territory remains one of the least understood parts of Australia.

All content on the blog is distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).