Public History in New South Wales

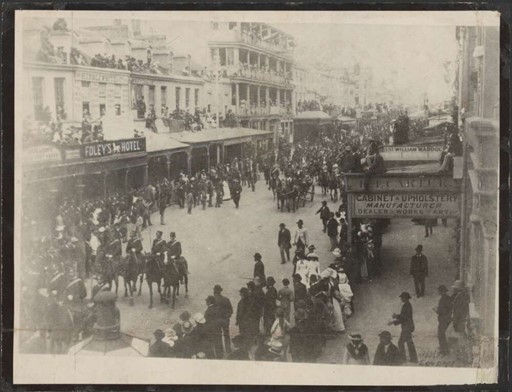

The practice of public history in New South Wales (NSW) can be traced back to the rise of the nation state. State governments began investing more and more in developing national identities and narratives as modern Australia evolved, particularly after 1945. Public institutions, monuments and rituals – including a national Australia Day – traced the wealth and progress of the country. They were critical in shaping popular historical consciousness.

People such as C.E.W. Bean (1879-1968) – who wrote On the Wool Track (1910) and was vitally involved in building the Anzac legend – became one of our first public historians. Though without formal academic training, Bean was a professional historian. For his generation, public history work – in historical societies, local museums, libraries, landscapes and archives – was done by amateurs.

The building and expansion of a secondary and tertiary education system from the 1960s encouraged the rise of specialisation in History related jobs both in and out of the academy. From the 1980s a new generation of freelance historians emerged. In 1985 the Professional Historians Association NSW Inc (PHA NSW & ACT) was formed. (A national body, Professional Historians Australia, was set up in 1996.) Three years later NSW’s first and by far the largest graduate public history program in NSW was established at the University of Technology Sydney. The course was taught by Ann Curthoys and Paula Hamilton. They were later joined by Heather Goodall and Paul Ashton and the Australian Centre for Public History was set up in 1999 to focus their projects and activities. Graduating over 150 Masters students and dozens of doctoral students, many of these public historians gained jobs in most of Australia’s leading cultural institutions. Others went freelance or set up their own consulting companies.

Public history programs and subjects were also offered at the University of NSW and the University of Sydney. Currently they are on offer at Macquarie University and the University of New England.

Public history today, broadly conceived, is practiced in New South Wales by a diverse range of people, groups and organisations. The PHA NSW & ACT has around 100 members. (There are about 150 academic historians in the state.) These public historians work in areas such as heritage, oral history, community history, native title, official history – histories commissioned by governmental agencies – corporate and institutional history, museums, history education – including textbook writing – and the media. Some are employed by government agencies such as the National Parks and Wildlife Service and the Australian War Memorial. Others are employed in heritage firms such as GML and Sue Rosen Associates. Public historians also work as academics, blending research and teaching with community engagement.

Public history contributes significantly to the state’s culture and economy through, among other things,

-

Cultural tourism

-

Community formation and development

-

Contributions to cultural institutions and infrastructure

-

Memory work

-

Advocacy and

-

Property development through heritage conservation and site interpretation

Public historians have also had important inputs into cultural institutions and infrastructure including the History Council of NSW and the Dictionary of Sydney. The refereed journal Public History Review has been Sydney-based since it commenced publication in 1992.

So what of the future? Public history is now a well-established field in NSW and Australia. It has a growing of body reflective and theoretical literature, the most recent of which is Making Histories (2020) edited by Paul Ashton, Tanya Evans and Paula Hamilton. (It is the first volume in de Gruyter’s new series Public History in International Perspective.) Public historians have a modest but significant presence in the state’s heritage industry. Many commissioned histories – of local government areas, corporations, NGOs, clubs, associations and industries – are written by public historians.

The main path for public history in the medium term lies in these types of external activities. Opportunities will be limited in both cultural institutions encumbered with shrinking budgets and the tertiary education sector where the humanities is, for the moment, in decline. The days of the lone freelancer may also be numbered. Public historians might be better placed to work in firms or be commercially networked with each other as well as other professionals. They need to enhance their presence in activities that work with the past in the present. And to ensure a stronger profile, they need to be explicit and vocal about the social benefits of public history and to work across different media.

All content on the blog is distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license (CC BY-SA 4.0).